Alicia Caticha (Northwestern University)

In memory of Doris Garraway

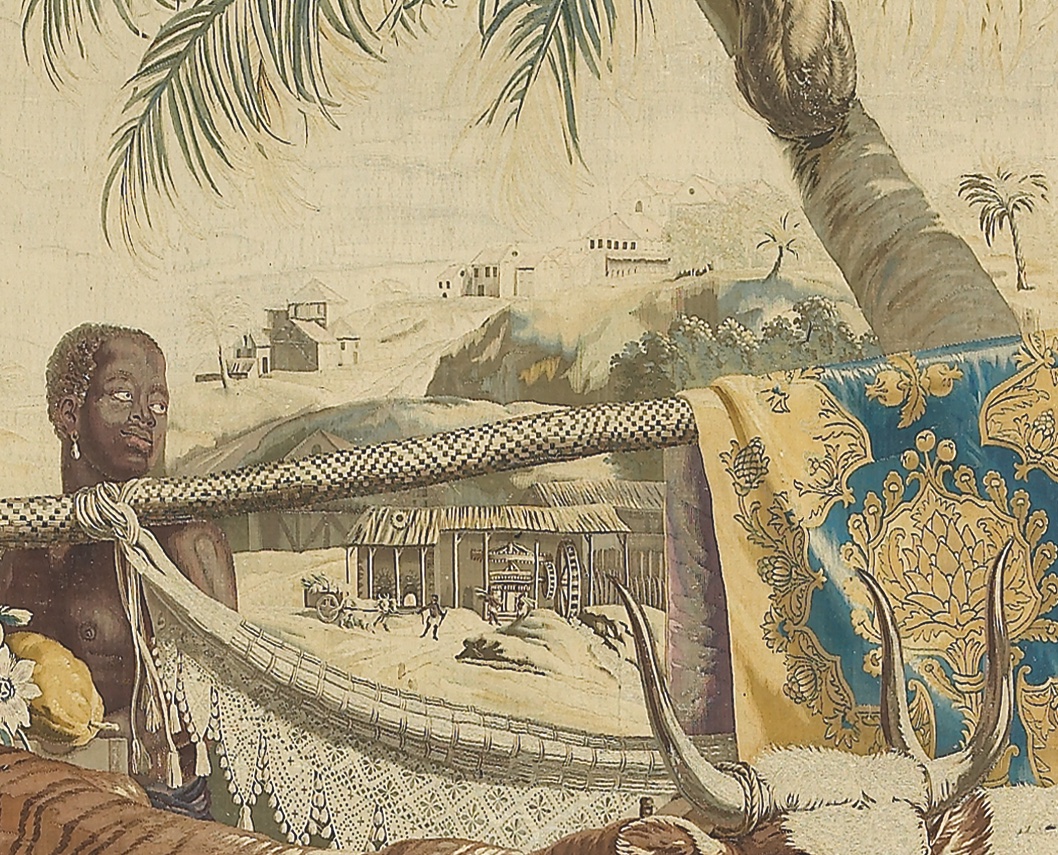

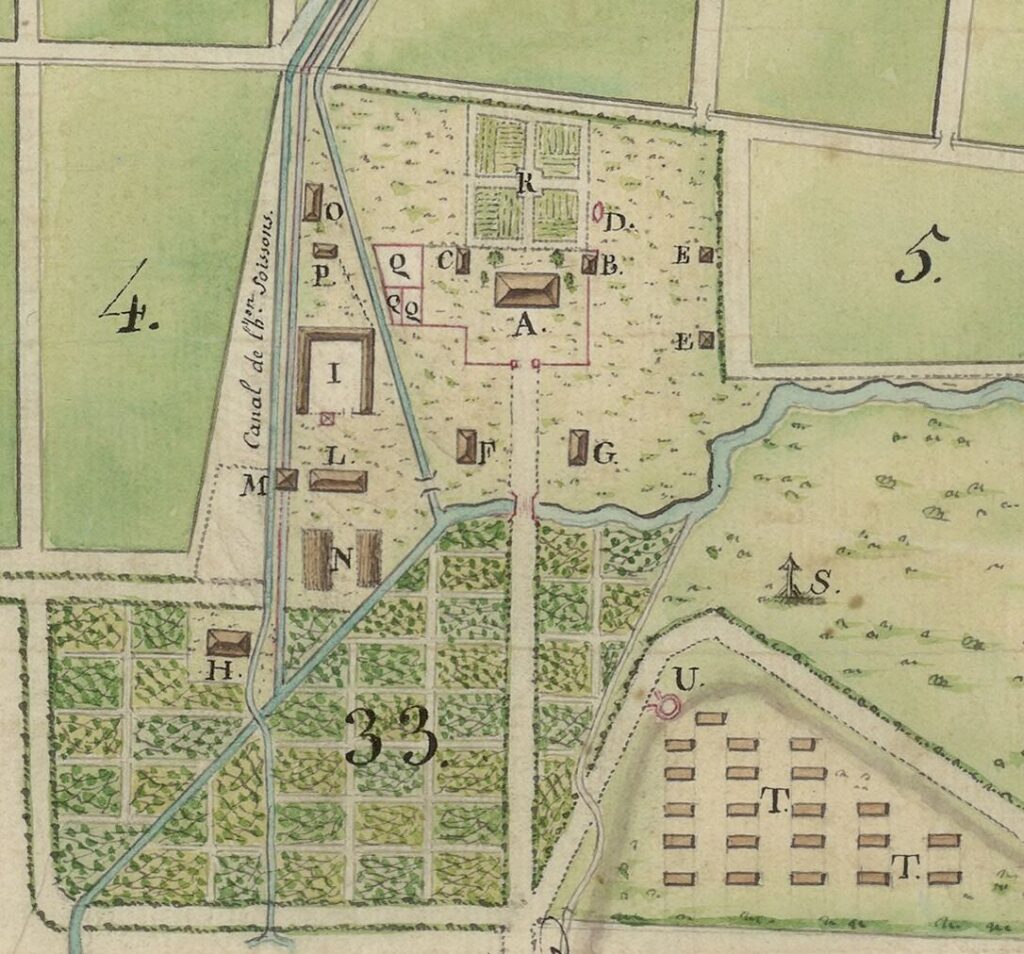

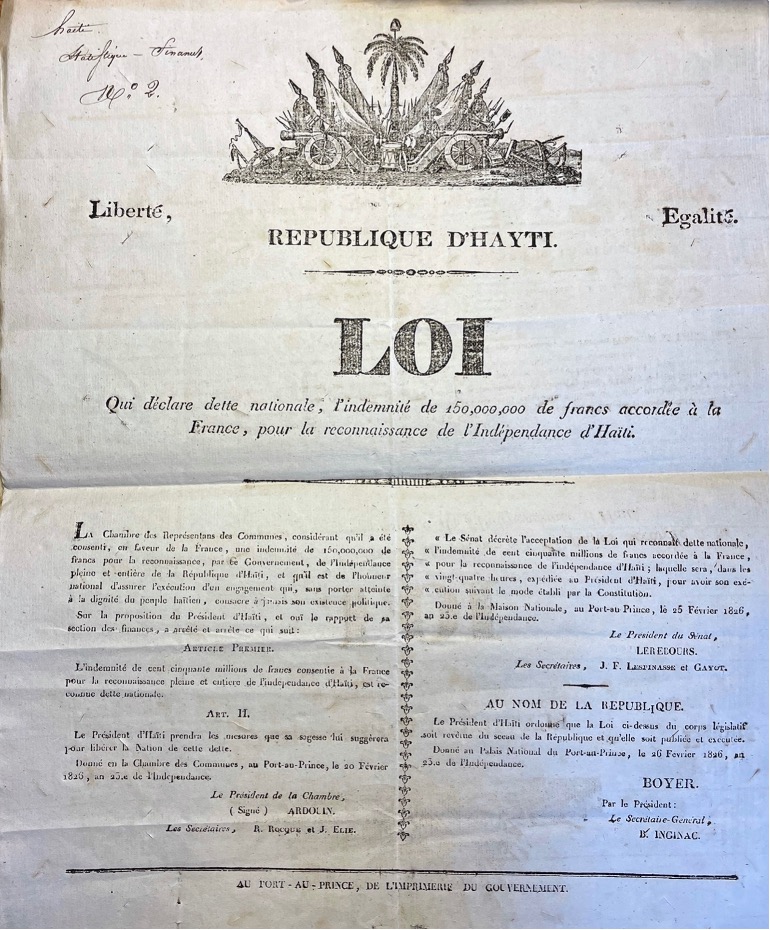

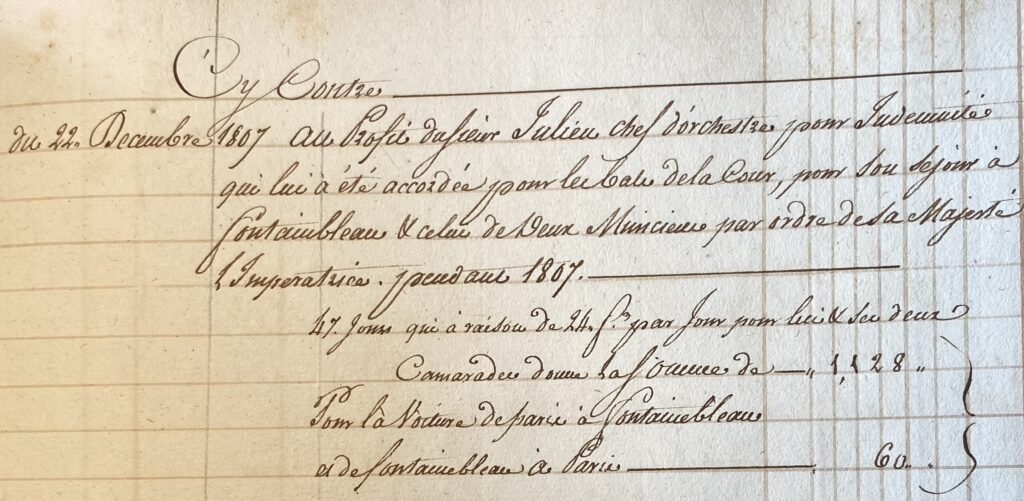

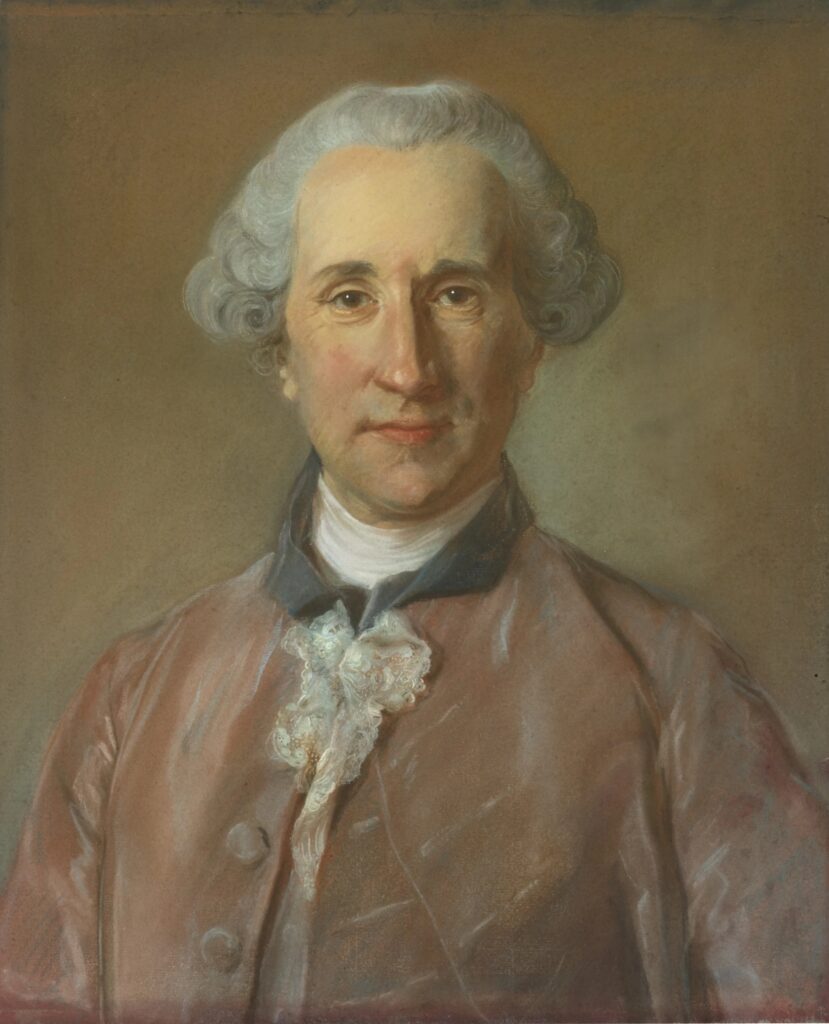

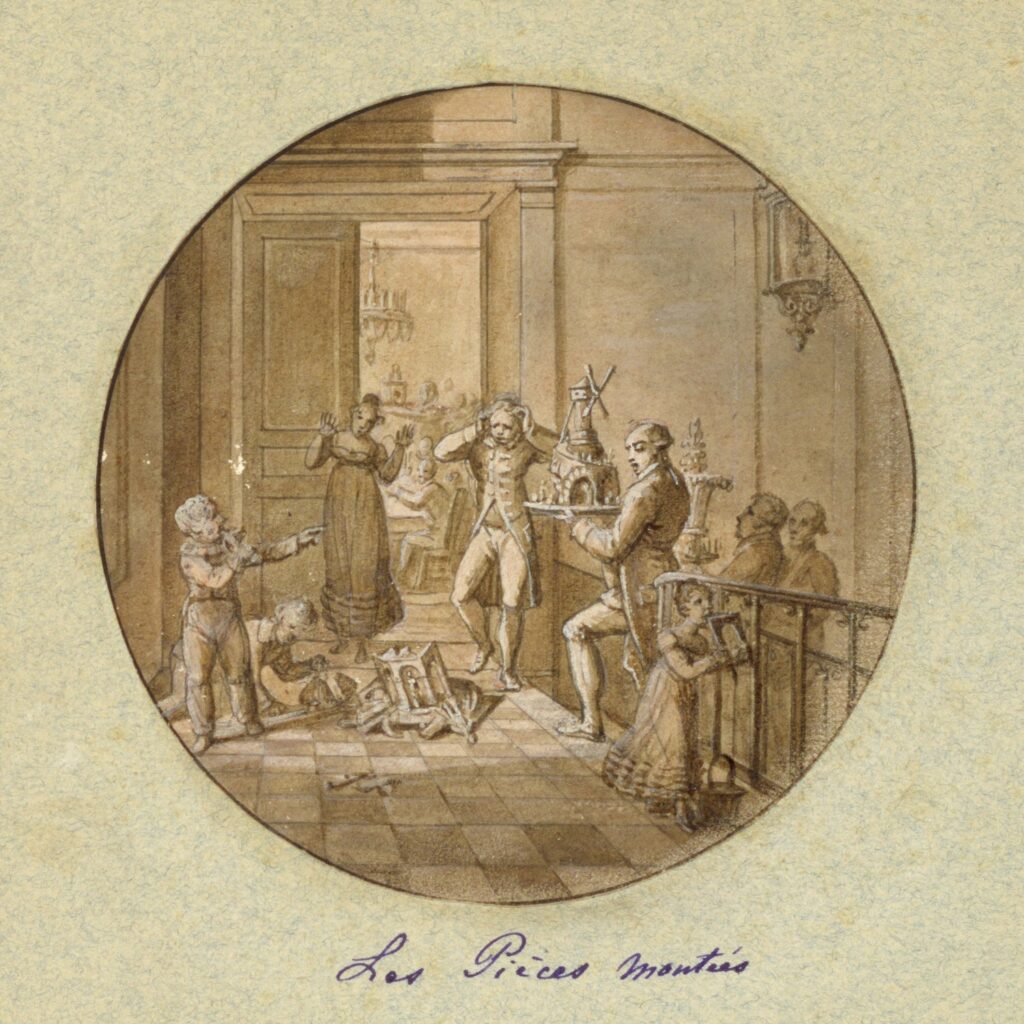

In 1820, Jean Charles Develly produced a series of drawings of various “objets de dessert” for a porcelain service by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory. The subjects of his designs, each to be transferred onto porcelain plates, included the production and sale of tartelettes, ice cream, biscuits, noisettes, marmalades, dragées, and, notably, cane sugar (Fig. 1). Produced in the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) and Louis XVIII’s abolishment of the slave trade in 1818, the cane sugar plate is imbued with abolitionist sentiment. At the plate’s center is a Black man cutting a sugar loaf while instructing two white children on the horrors of slavery. He gestures towards a painting of a sugar plantation in which the silhouette of an overseer brandishes a whip above a supplicant figure whom we may presume is an enslaved field hand. The cane sugar plate is in striking contrast to the rest of the series, which features more palatable, lighthearted subjects including children indulging in tarts at a confectioner’s shop and the folly of a tiered cake (pièce montée) dropped on the floor (Fig. 2). The violence of enslaved labor inherent in the production of sugar is displayed not only for the fictional children depicted in the scene, but also for the elite French diner who consumes sugared delicacies directly from this porcelain service.

At first glance, the Black man’s presence appears to be a device on the part of Jean Charles Develly to link the sugared delicacies of the dessert service to sugar’s violent origins. Yet the man’s neatly tailored dress and tidy surroundings suggest the location of the scene is not just a confectioner’s shop but a well-to-do boutique in metropolitan France. Although we do not know the man’s free or enslaved status—slavery would not be abolished in the French empire until 1848—we may conjecture that he is a confectioner in his own right. Indeed, Develly’s design is testament to the little-known history of enslaved confectioners on both sides of the Atlantic.

Given that professionals trained in the delicate art of confectionary were hard to come by in the Americas, it became a symbol of affluence and cultural refinement to send an enslaved person to France for training. The most cited example is that of James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved chef who accompanied him to France from 1784 to 1789. Although Hemings’ culinary training has been well studied by historians, particularly in relation to Jefferson’s own admiration of French culture and cuisine, Hemings’ knowledge of the confectionary arts has been largely sidelined.[1] After completing his culinary studies, Hemings divided his time between Paris and Chantilly, where he studied confectionary in the kitchen of Louis Joseph, the Prince of Condé.[2]

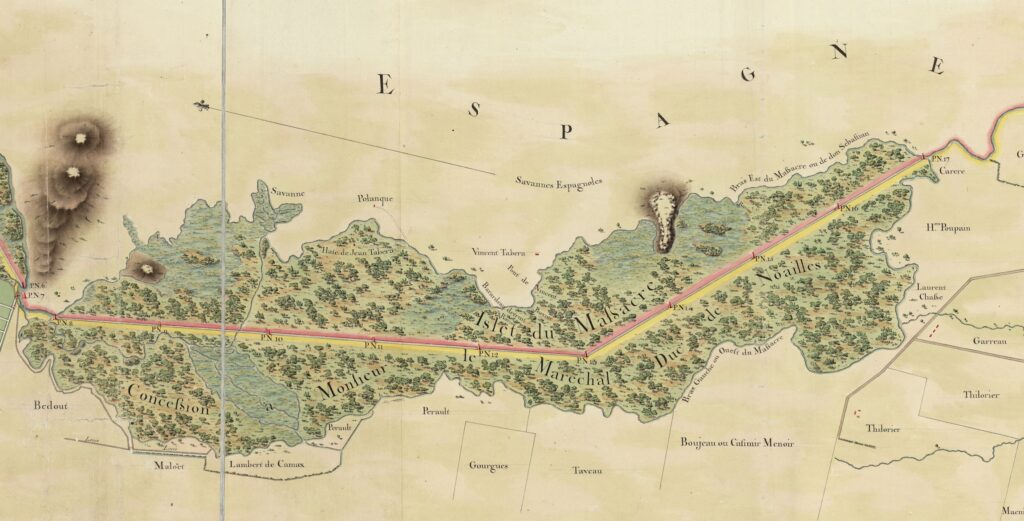

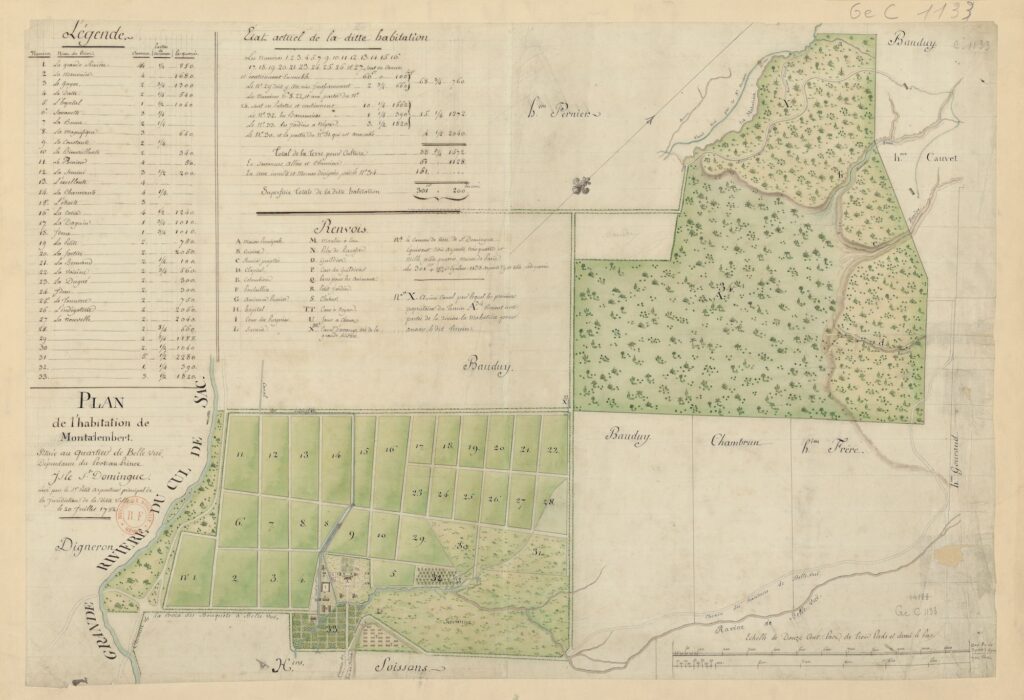

Less is known about confectioners—enslaved or free, Black or white—in Saint-Domingue, and the French Antilles more broadly. What is clear is that in the wake of the Seven Years’ War, as colonial elites in Saint-Domingue aimed to emphasize their cultural and racial affinity with the metropole, confectioners existed in increasing numbers.[3] The inventory of the mixed-race indigo plantation owner Julien Raimond records, among his many possessions for the dining table, an enslaved individual who had been trained as a pastry chef.[4] Raimond’s well-set dining table served as a physical and cultural manifestation of his good taste, and, by extension, his whiteness.[5] Indeed, it was not until the 1770s, when increasingly harsh legal definitions of biological race were instated in the colony, that Julien Raimond’s whiteness was revoked and he was re-categorized in legal documents as a “quarteron.”[6] The term indicated Raimond was a person of color and, more specifically, that one of his four grandparents was of African descent.

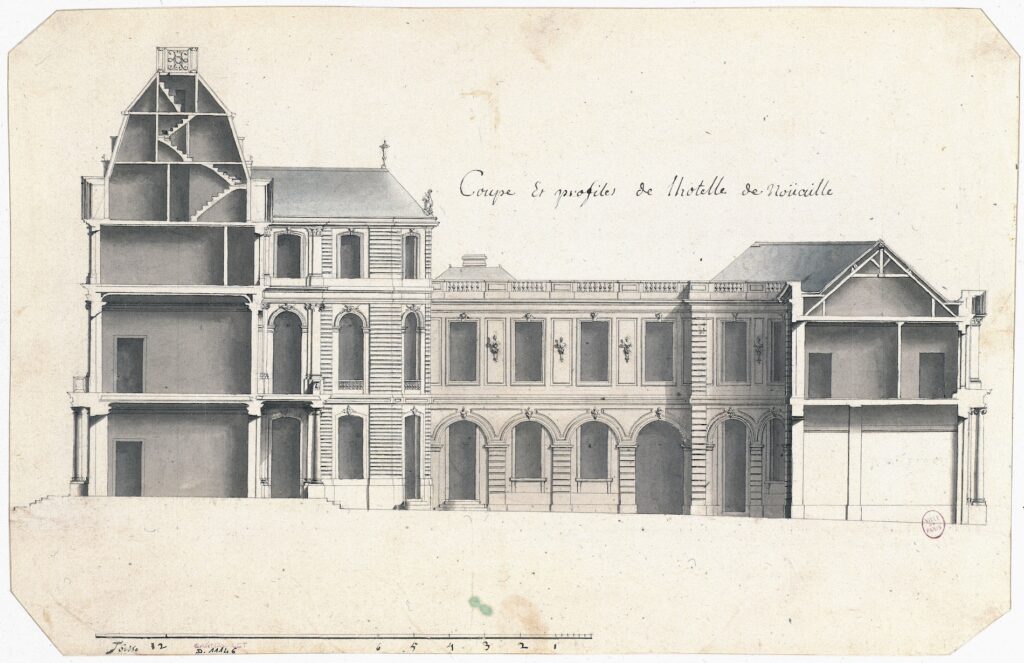

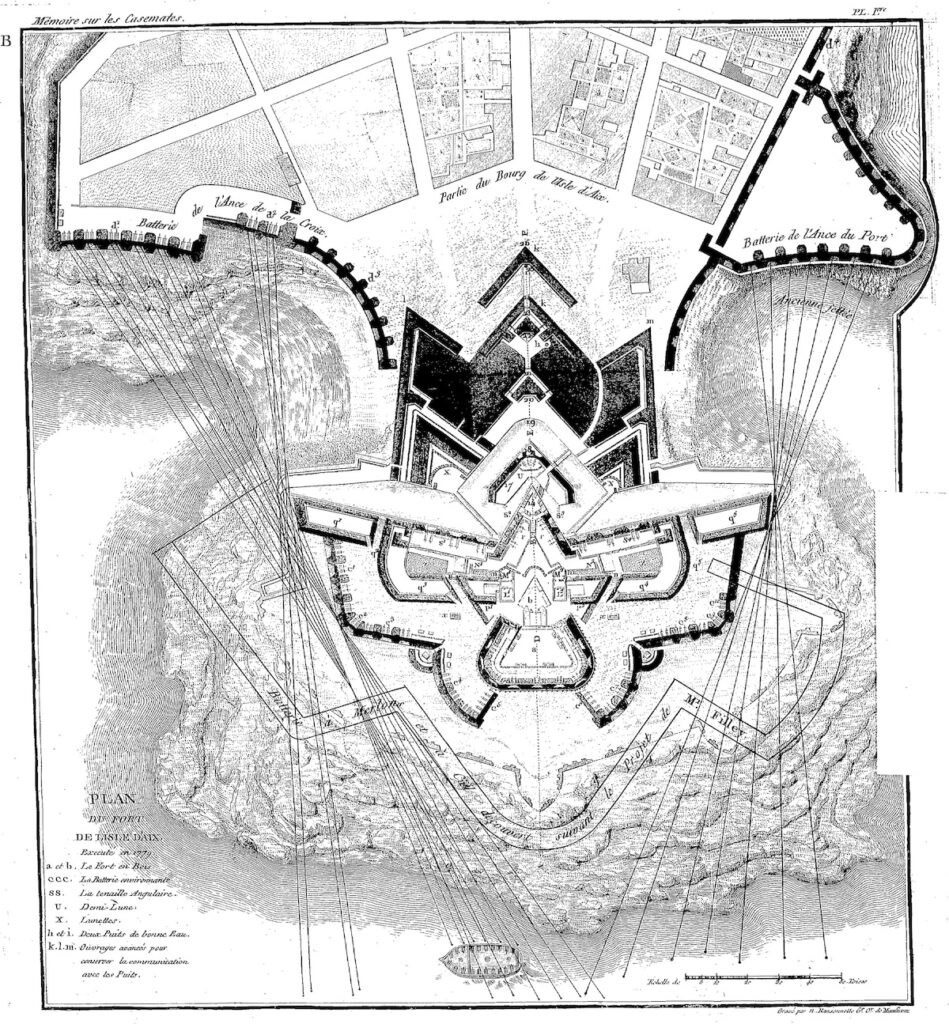

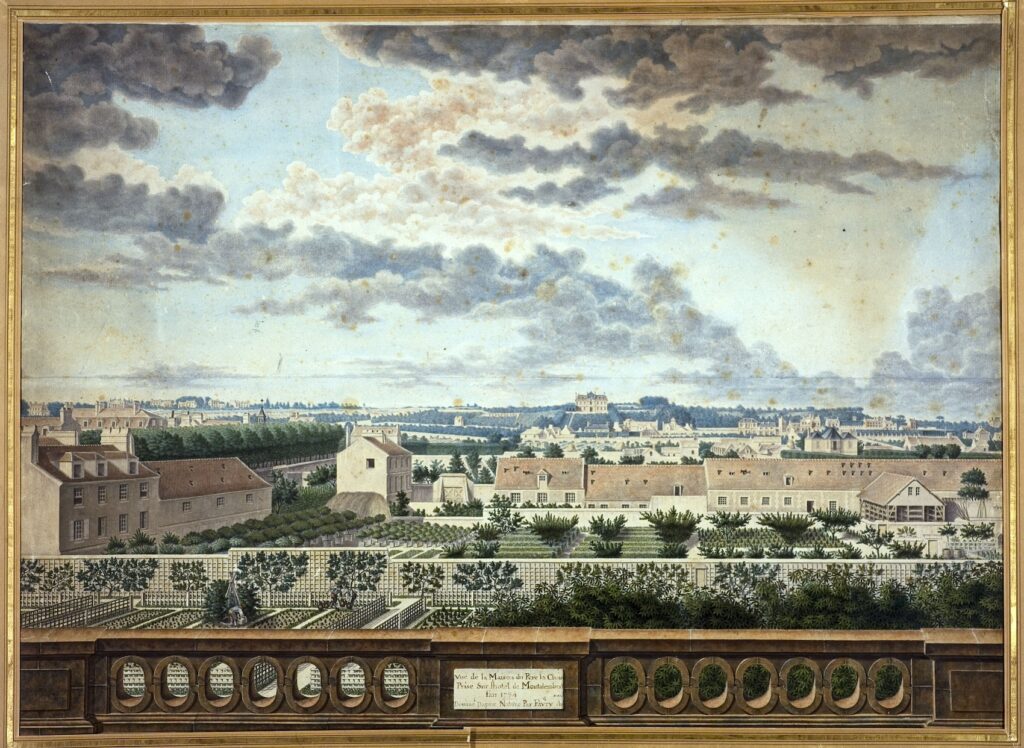

Plantation owning families deemed suitably white aimed to distance themselves from mixed-race, white-passing elites such as Julien Raimond. Yet even their whiteness was called into question upon travel to metropolitan France. Although they were considered to be at the top of the racial and class hierarchy in Saint-Domingue, in France white Creoles were socially tainted by their immediate proximity to Blackness. Subscribing to an intricately constructed culture of taste—one in which the material culture and performance of dining factored predominantly—was but one strategy of assimilation.[7] The patronage of sumptuous sculptural confections transposed the most exalted dining customs of Paris into the public and private spaces of the Creole plantation class. Pièces montées and white sugar-paste pastillage figurines depicting pastoral, chinoiserie, and antique subjects became a way for colonial government officials and plantation owners alike to celebrate and demonstrate their affinity to a white Parisian elite.[8] Although no images of the colonial table survive, the French confectioner Joseph Gilliers’s manual on the dessert course documents for posterity such elaborate sculptural constructions (Fig. 3).

The Parisian confectioner’s most impressive architectural and sculptural works were made from sucre royale, the whitest of all types of sugar and refined exclusively in France. Yet the market for sucre royale, which was prohibitively expensive and made from the highest quality raw materials, was limited to Paris and Versailles. To my knowledge, French refiners did not ship the rarefied commodity back to the colonies for sale. As such, it is very likely that confectioners and refiners in Saint-Domingue, like many of their metropolitan French counterparts, fabricated sucre terré, a “lesser” refined sugar, to appear as white, transparent, and crystalline as sucre royale.[9] In doing so, they would have played directly into the hands of French refiners, customs agents, and consumers whose increasing anxiety regarding the “purity” and authenticity of sugar coming from Saint-Domingue mirrored similar fears that the French would become a race of sang-mêlés (“mixed-bloods”).[10]

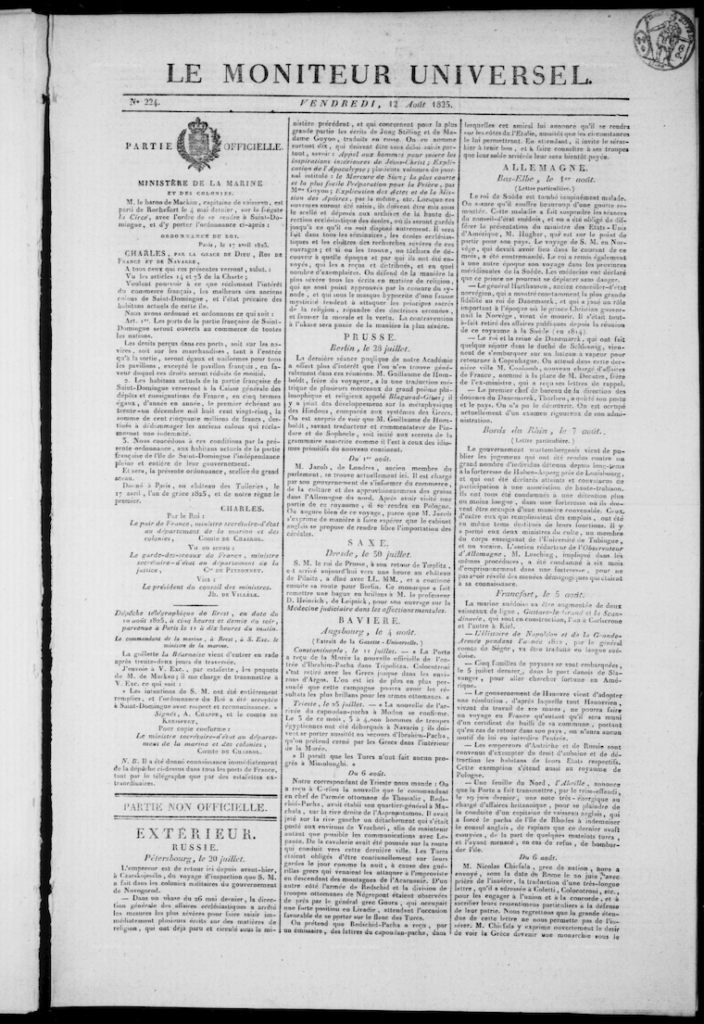

Nevertheless, the commitment to metropolitan French banqueting traditions—and its attendant associations with an increasingly rigid understanding of racialized whiteness—is evident throughout the pages of Saint-Domingue’s first commercial broadsheet, the Affiches américaines. In 1773, the confectioner and distiller Sieur Blenon advertised a recent shipment of goods received directly from France, which included “the latest and most fashionable surtouts [centerpieces], which he will display fully decorated in his shop a few days before and after New Year’s Day.”[11] In 1780, the confectioners Sieurs Blanc & Courrieradvertised the saleof biscuits coming directly from the Palais Royal in Paris.[12]

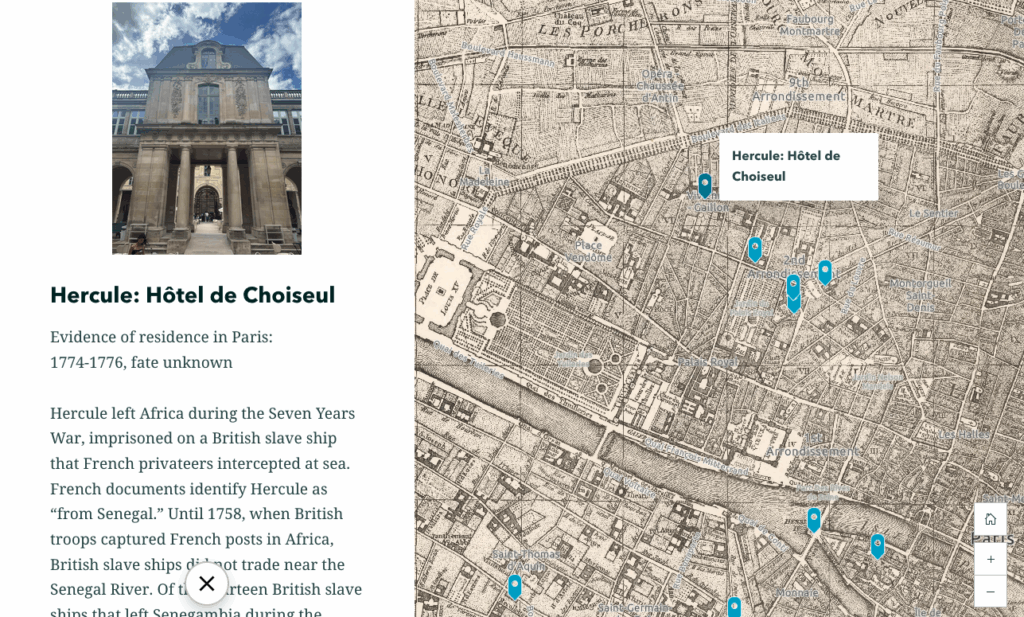

Most notable is the 1771 inventory sale of the Cap-Français boutique of the confectioner Sieur Bonnefond, located on the Rue Penthievre.[13] Conducted in preparation for his return to France, the inventory details the molds, glasses, and ceramic wares for over 180 table settings. The molds for sugar sculptures included “Chinese subjects, the four seasons in both large and small sizes; a shepherd and shepherdess; sheep and dogs in different poses; architectural features including columns and arches; a fury with her attributes; Venus and Apollo; two satyrs; two dozen smallcupids and shepherds.”[14] In addition to the “various utensils and tools related to confectionary,” the inventory also includes “three Nègres, of which two are excellent confectioners and druggists, & the other, a good cook; also two Négresses, of which one is a good cook, laundress, and governess & the other, a good laundress and seamstress.”[15] We know little of the “three Nègres” and “two Négresses” listed in Bonnefond’s inventory, not even their names. Indeed, most enslaved confectioners in Saint-Domingue survive for posterity as anonymous lines in ledgers. One notable exception was the confectioner la Douceur, or “Sweetness.” Yet even his name effaced his individual identity and conflated him with his labor.[16]

Given the brief description of the two “excellent confectioners” in Bonnefond’s inventory, we can only glean the vaguest contours of their life and art. As confectioners working in Cap-Français, they would have had increased value for a white Creole elite interested in performing Frenchness. This would in turn ensure that the enslaved confectioner was placed in a hierarchy above other enslaved individuals in Cap-François, and certainly above the enslaved plantation field hand in rural Saint-Domingue. In terms of their artistry, we can only speculate that they had a hand in constructing and filling the molds of Venus and Apollo, of chinoiserie subjects, of delightful animals, with a white sugar pastillage. We can only imagine that the 180 place settings that they likely had a hand in making and maintaining were those cited in a description of a 1769 banquet held by the Fathers of Charity in Cap-Français: “For lunch and dinner [the Fathers] built a rustic salon champêtre, artistically made, ornamented with greenery and flowers and very well illuminated, in which they set up a table with one hundred place settings. We saw a shell grotto in a hollow, in the middle of which was a fountain seven to eight feet tall […]”[17] Such a centerpiece fountain would have been a feat of great proportions, particularly in the Caribbean heat. It would have required a highly skilled confectioner trained not only in the arts of sugar and pastry, but also in paper mâché, porcelain, and other materials used in the fabrication of ephemeral architecture.

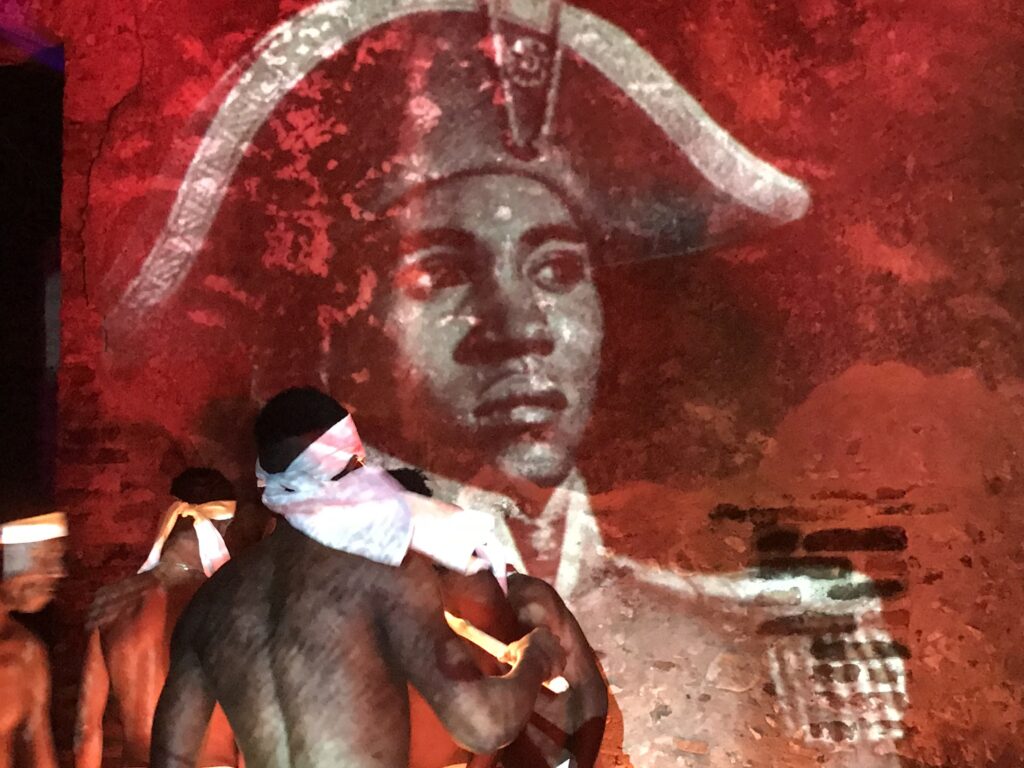

Certainly, the ideological significance of sugar sculptures—often displays of political and princely power in early modern Europe—shifted when made by enslaved confectioners and displayed in such proximity to the locus of sugarcane’s agricultural origins.[18] Without the temporal and geographic distance proffered by the Atlantic Ocean, the confectioners’ art was explicitly implicated in the brutality of the sugar plantation. I would go so far as to suggest that visually and physically consuming figural sugar in Saint-Domingue was a form of cannibalism.[19] The very charge that Europeans placed on Africans and indigenous Caribs to justify their enslavement, cannibalism metaphorically underwrote the Caribbean slave economy through daily acts of violence in which the Black body was objectified and consumed.[20] Writing in the English tradition, Olaudah Equiano stated as much in his famous description of the Middle Passage: “I asked them if we were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and long hair?”[21] The English abolitionist William Fox cited an unknown French writer who had observed “that he cannot look on a piece of sugar without conceiving it stained with spots of human blood.”[22]

As Doris Garraway has illustrated, French colonial rhetoric surrounding cannibalism was laden with desire for the racial other. The missionary Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre imagined his own cannibalism at the hands of the Caribs in terms that displace the fantasy of colonial desire onto the abject. French flesh, Du Tertre claims to have heard, was “the best and the most delicate.”[23] The desire for and consumption of the “delicate” art of sugar sculpture and pastry thus makes explicit the politics of sugar consumption not just on Saint-Domingue, but across the Atlantic as well.[24] Recalling the enslaved confectioner la Douceur, the desire for sugar is transcribed onto his body. Whether sexual or gustatorial in meaning, his name suggests that he too is sweet and ripe for consumption. Indeed, the spots of human blood imagined by the anonymous French writer were not only cannibalistic; they were illustrative of what the practice of sugar sculpture and increasingly rigid colonial laws of racial segregation could not avoid. Saint-Domingue’s increasingly mixed-race society was the result of cross-racial sexual desire, the truth of which could not be sugarcoated or effaced. It is tempting to return to the Develly’s Sèvres plate of 1830 as a tidy resolution to the unsettling cannibalistic violence of the confectionary arts. The elegant rendering of the Black confectioner illustrates a fantasy of progress, in which the enslaved fieldworker has become the confectioner, and the enslaved confectioner has become his own master. But as Saidiya Hartman reminds us, “the loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them. So it is tempting to fill in the gaps and to provide closure where there is none.”[25] Develly’s plate is such a fiction.

[1] A notable exception is Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (W.W. Norton & Company, 2008), 155-209.

[2] Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello, 156-66.

[3] Jennifer L. Palmer, Intimate Bonds: Family and Slavery in the French Atlantic (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 27.

[4] John D. Garrigus, Before Haiti: Race and Citizenship in French Saint-Domingue (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 1-8.

[5] On the relationship between taste and Creole racial hierarchies in Saint-Domingue, see Madeline L. Zehnder, “Revolutions of Taste: Mon Odyssée and the Aesthetic Inheritance of Saint-Domingue,” American Literary History 31, no. 1 (2019): 1–23.

[6] Humiliated by this change in circumstances, Raimond returned to France in the 1780s to advocate for racial reform (notably not abolition) in the colonies. Florence Gauthier, L’aristocratie de l’épiderme: Le combat de la Société des Citoyens de Couleur, 1789-1791 (CNRS Editions, 2007), 21-31. On the legal evolution of race in Saint-Domingue in the wake of the Seven Year’s War see, Garrigus, Before Haiti, 110-70.

[7] Simon Gikandi’s theorization on the mutual construction of British ideas on taste, whiteness, and the economic system of Atlantic slavery can be transposed to the French context. Simon Gikandi, Slavery and the Culture of Taste (Princeton University Press, 2011), particularly 80-92.

[8] On the political uses of edible art, see Jérémie Koering, Iconophages: A History of Ingesting Images (Zone Books, 2024), 287-96.

[9] Maud Villeret, Le goût de l’or blanc: le sucre en France au XVIIIe siècle (PU Rennes, 2017), 153-8.

[10] Alicia Caticha, “Material Masquerade: Porcelain, Sugar, and Race on the Eighteenth-Century French Dining Table,” Art History 47, no. 3 (2024): 593-4.

[11] “Le Sr Belnon, Marchand Confiseur & Distillateur, rue Notre-Dame, au Cap, donne avis qu’il a récus de France des Surtouts du dernier goût & des plus à la mode pour garner les tables,” Affiches américaines, 18 décembre 1773.

[12] Affiches américaines, 13 juin 1780. It should be noted that all these confectioners were easily identifiable as “legally white” due to the honorific “Sieur”, which became a signifier of race, rather than class, in the 1770s and further testifies to the increasingly rigid categorization of race in Saint-Domingue after the Seven Years’ War.

[13] Bonnefond’s address is listed in the Affiches américaines, 1 juin 1771.

[14] “180 couverts; un boucaut de moules à figure, pour décorer les desserts; histoires Chinoises; les quatre saisons en grand & en ptit; un berger & une bergère; plusieurs moutons & chines, de différentes attitudes; colones & ceintres; une furie avec ses attributes; Venus & Apollon; deux Satyres, deux douzaines de petits amours & bergers […]” Affiches américaines, 16 janvier 1771.

[15] “[…] toutes sortes d’untensiles relatifs audit état: en outre, trois Negres, dont deux bons Confiseurs & Droguistes, & l’ature, bon Cuisinier; plus, deux Négresses, dont une bonne Confiseuse, Blanchisseuse, & Gouvernante & l’autre, bonne Blanchisseuse & Couturiere.” Affiches américaines, 16 janvier 1771.

[16] Affiches américaines, 16 mai 1789. Another exception is Louis, the confectioner to the former Intendant of Saint-Domingue, M. de Montarcher. Affiches américaines, 25 juin 1774.

[17] Affiches américaines, 21 mars 1770.

[18] On festivals and the ephemeral art of dining in early modern Europe, see Marcia Reed, The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals (Getty Research Institute, 2015).

[19] My thinking on this subject is informed by Carlyle Van Thompson, Eating the Black Body: Miscegenation as Sexual Consumption in African American Literature and Culture (Peter Lang, 2006).

[20] Although I deploy cannibalism as a metaphor, there are multiple maritime disasters in which the enslaved were known to be cannibalized by their captors. The most famous is documented for posterity in Pierre Viaud, Naufrage et aventures de M. Pierre Viaud, natif de Bordeaux […] histoire veritable vérifiée sur l’attestation de M. Seventeenham, commandant du fort Saint-Marc des Appalaches (Avignon: Offray fils, 1827), 89. Also see Vincent Woodard, The Delectable Negro: Human Consumption and Homoeroticism within U.S. Slave Culture (New York University Press, 2014).

[21] Carl Plasa, “‘Stained with Spots of Human Blood:’ Sugar, Abolition and Cannibalism,” Atlantic Studies 4, no. 2 (2007): 231.

[22] Plasa, “Stained with Spots,” 234.

[23] Doris Garraway, The Libertine Colony: Creolization in the Early French Caribbean (Duke University Press, 2005), 154-5.

[24] Although many sugar sculptures were not intended to be eaten, they nonetheless played with a viewer’s senses, bringing together sight, smell, and taste to create a synesthetic event.

[25] Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe: A Journal of Criticism., no. 26 (2008): 8.

Cite this post as: Alicia Caticha, “Sugarcoating Slavery: Enslaved Confectioners in Saint-Domingue,” Colonial Networks (March 2026), https://www.colonialnetworks.org/?p=958.