Oliver Wunsch (Boston College)

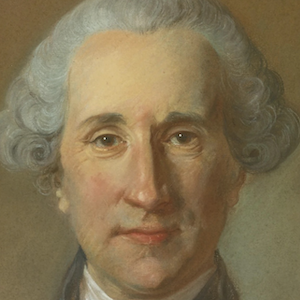

In a pastel portrait by Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, an array of colors define the face of the French plantation owner Aimé-Benjamin Fleuriau (1709–1787) (Fig. 1). A shadow of bluish grays and earthen browns creeps across his right side. On the left, yellow striations give his jaw a warm glow. Touches of pink dash across his cheek and nose, suggesting the blood pulsing beneath the surface. Step close to the pastel and you will count many more colors, flesh disaggregating into discrete deposits of wide-ranging pigments.

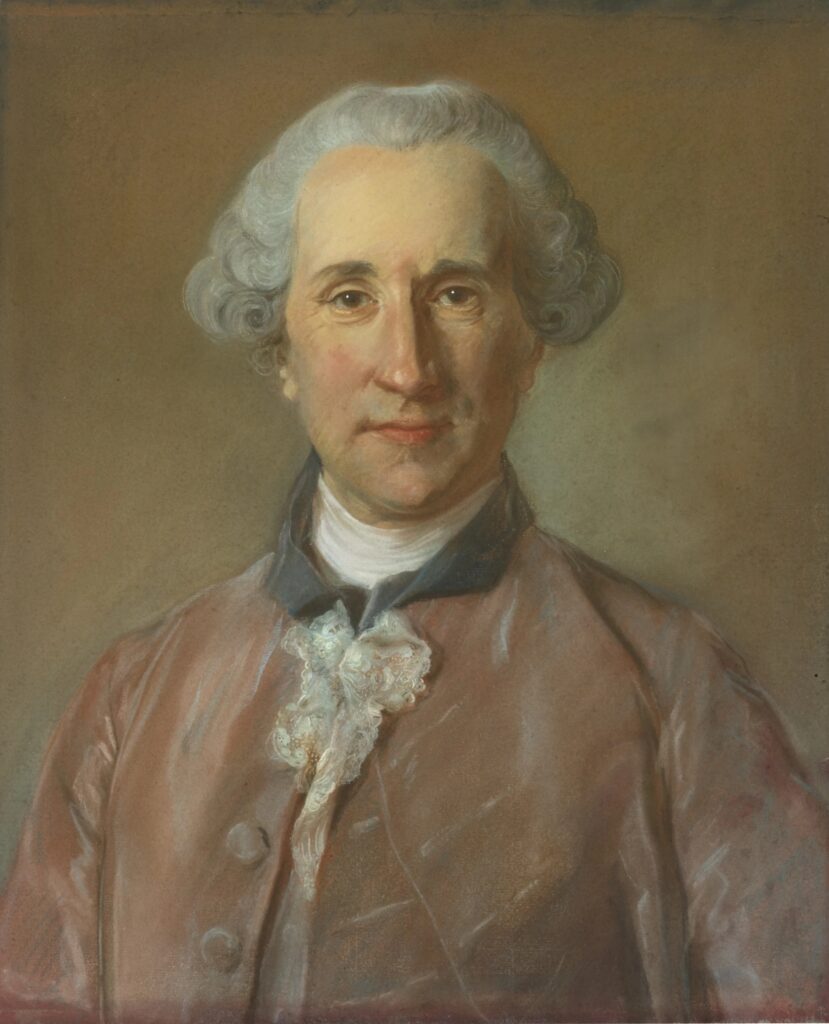

In the eyes of the law, however, Fleuriau was white, and this fact determined much about his life. Thanks to Jennifer L. Palmer’s careful study of family relationships in the French Atlantic, we know much of Fleuriau’s biography.[1] Born in La Rochelle to a bankrupt sugar refiner, he sought fortune abroad, arriving in the French colony of Saint-Domingue around 1729. There, he built a prosperous career, organizing the sale of enslaved people, then buying his own sugar plantation in the plain of Cul-de-Sac, to the east of Port-au-Prince. A perspectival map of the plantation from 1753 shows both its considerable acreage and, in the left foreground, the enslaved people whose labor allowed Fleuriau to profit (Fig. 2). Exaggerated in size relative to the land, the figures collect cane extract from an ornately rendered sugar mill, whose shell-like structure transforms the brutal realities of their work into a Rococo fantasy.

When Fleuriau returned to La Rochelle in 1755, he used his newfound wealth to rise into the upper echelons of French society, marrying Marie-Anne-Suzanne Liège, a young woman from a prominent merchant family. At the same time, Fleuriau remained intimately connected to the life he had led in Saint-Domingue, most notably through the children he had fathered with a woman of color named Jeanne Guimbelot, whom he had once enslaved. Five of these children joined him in France. Named Joseph, Paul, Jean, Marie, and Charlotte, they all carried the surname “Mandron,” and Fleuriau did not acknowledge paternity of them once they arrived in France.[2] He nonetheless sought to maintain their connection with his family and to guarantee their freedom—a pressing matter at a time when French law increasingly equated Blackness with enslavement.[3]

To what extent do these biographical facts bear on Perronneau’s portrait of Fleuriau? Can we “map” Fleuriau’s entanglement with Saint-Domingue and slavery onto the portrait? Commissioned along with a pendant portrait of his wife Marie-Anne-Suzanne on the occasion of their marriage in 1755, the pastel marked the moment in Fleuriau’s life when he sought to reintegrate himself within the elite merchant class of La Rochelle (Fig. 3). As Dominique d’Arnoult has noted, Fleuriau likely saw the portrait as part of the “social rehabilitation” of his family after the embarrassing bankruptcy of his father a generation earlier, a purchase made to signal his reentry into the world of respectable appearances.[4] Pastel portraits served as fashionable tokens of power and prestige in this milieu, their fragile materiality evoking the courtly délicatesse that the newly affluent sought to cultivate.[5] Perronneau fulfilled numerous commissions for the merchants and financiers on the western coast of France, many of whom derived their fortunes from colonial investments and the slave trade.[6] In that respect, these portraits owed their existence to the plantation economy and the systems of exploitation that undergirded it.

It is tempting to stretch the connection further, to argue that the varied tonalities in Perronneau’s depiction of Fleuriau relate in some way to the intertwined lineages that defined his familial identity or the eighteenth-century racialization of skin color more broadly. Perronneau’s attention to the material subtleties of Fleuriau’s complexion could, for example, be interpreted as a product of what Angela Rosenthal described as an eighteenth-century European belief in the “talkative” legibility of white complexion, whose capacity to blush was implicitly or explicitly contrasted with the supposed “muteness” of Black skin.[7] On the other hand, the variegated marks of the pastel crayon could be taken as a challenge to the binary opposition of white and Black. As Anne Lafont has recently observed in her examination of Watteau’s trois crayons head studies of a white woman and a Black child, the nuanced materiality of a carefully rendered portrait can reveal the reductiveness of racial terminology, particularly in works made of friable pigments that blur the semantic distinction between white and Black.[8]

But in contemplating the possible connections between Fleuriau’s portrait and his interracial family, I am reluctant to assume a direct relationship between the two. Artistic conventions from the period militate against reading the polychromatic streaks of Perronneau’s pastels as straightforward statements about skin itself. Roger de Piles, for example, argued in his Cours de peinture par principes (1708) that portraitists should not replicate the actual appearance of skin, recommending instead that they exaggerate the contrast between patches of different colors to create pleasing flesh tones that blend together only when seen from a distance:

A painter who only renders what he sees will never achieve a perfect imitation, because if his work appears good to him from close and on the easel, from a distance it will displease others and often the artist himself: a tone that from close appears distinct and a certain color will appear another color from a distance and blend into the mass of which it is part. Therefore if you wish your work to make a strong impression from the place where it is supposed to be seen, the colors and lights should be a little exaggerated.[9]

Artists of the subsequent generation would elaborate on this advice, distinguishing the materiality of a portrait from the physical character of its referent. In a lecture on portraiture to the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture from 1750, the painter Louis Tocqué argued that the flesh tones in a portrait should not directly reproduce the materiality of flesh: “if you limit yourself to the material aspect, you fall into that coldness and bland neatness which reduce the artist to the level of a mere craftsman, and the paintings you produce will typically be either the color of bronze or of ivory.”[10] Tocqué instead advised portraitists to paint with “sentiment in the brush” and “to make yourselves masters of your touch,” granting the color and light of a painting a degree of autonomy from the subject that they represent. For Tocqué, it was this refusal “to limit yourself to the material aspect” that separated the artist from the “mere craftsman,” ennobling the act of making.

This socially elevated understanding of a portrait’s materiality held value to the artist and sitter alike. For Fleuriau, eager to rise within the ranks of French society and aspiring toward a noble title, an appreciation for the transcendent subtleties of aesthetic experience was de rigueur.[11] As Brice Martinetti has shown, the eighteenth-century merchants of La Rochelle carefully modeled their consumption and collecting practices on habits they associated with the court aristocracy.[12] The largely Protestant merchant class of La Rochelle, including the Fleuriaus, showed little propensity for the austerity traditionally associated with their faith. The Rochelais embraced the latest fashions in art and architecture, generally conforming to the culture of the affluent elite in France’s other urban centers. Their homes sometimes included oblique references to the colonial origins of their wealth, such as the globe and navigational instruments in a gilded boiserie overdoor of the hôtel Fleuriau.[13] But these emblems of commerce were nonetheless expressed in a form that could just as easily be interpreted in terms of enlightened learning and good taste. They testify to what the Abbé Coyer described in 1756 as the desire among colonial merchants “to make people forget that they once engaged in trade.”[14]

The delicate materiality of a pastel portrait, in its capacity to evoke the delicate manners of the court nobility, offered merchants such as Fleuriau an ideal instrument for such strategic forgetting. Any attempt to find traces of Saint-Domingue in Perronneau’s portrait of Fleuriau therefore likely runs counter to the sitter’s intentions. Those traces may nonetheless be present. The pinks and crimsons that give Fleuriau’s cheeks and lips their vital warmth, for example, may well be made from carmine, a pigment derived from cochineal harvested largely by enslaved laborers in the Americas. Pastel treatises from the period particularly recommended the pigment for use in flesh tones because of its lively brilliance and relative permanence.[15] The exploitation and violence that went into the production of the material became, in the downy powder of pastel portraiture, all but invisible. If the substance is present in Perronneau’s depiction of Fleuriau’s skin, the very obscurity of its origins is perhaps fitting, imperceptibly connecting the portrait to a world that Fleuriau now wished to keep at a distance. Art can be both a site of colonial entanglement and a tool for its disavowal.

[1] Jennifer L. Palmer, Intimate Bonds: Family and Slavery in the French Atlantic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 129–57.

[2] On the lives of these children, see the information compiled by Olivier Caudron in Érick Noël, ed., Dictionnaire des gens de couleur dans la France moderne, vol. 3, 3 vols. (Geneva: Droz, 2017), 854–60. See also Palmer, Intimate Bonds, 140–46.

[3] Palmer, Intimate Bonds, 140–42.

[4] Dominique d’Arnoult, Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, ca. 1715-1783: un portraitiste dans l’Europe des Lumières (Paris: Arthéna, 2014), 260.

[5] On pastel’s delicacy as a means of connoting social délicatesse, see Oliver Wunsch, A Delicate Matter: Art, Fragility, and Consumption in Eighteenth-Century France (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024).

[6] Perronneau’s multiple portraits of the Journu family are the most conspicuous examples. See Melissa Hyde, “Men in Pink: The Petit-Maître, Refined Masculinity, and Whiteness,” Journal18, no. 17 (2024), https://www.journal18.org/7284.

[7] Angela Rosenthal, “Visceral Culture: Blushing and the Legibility of Whiteness in Eighteenth-Century British Portraiture,” Art History 24, no. 4 (2004): 563–92.

[8] Anne Lafont, “Blackness Is in the Making: Materials of the 18th-Century Artist” (Getty Research Institute, December 6, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sg_TkfxlIpM&t.

[9] “Un peintre qui ne fait que ce qu’il voit, n’arrivera jamais à une parfaite imitation : car si son ouvrage lui semble bon de près, et sur son chevalet, de loin il déplaira aux autres et souvent à lui-même: une teinte qui de près paraît séparée et d’une certaine couleur, paraîtra d’une autre couler dans sa distance, et se confondra dans la masse dont elle fait partie. Si vous voulez donc que votre ouvrage fasse un bon effet du lieu d’où il doit être vu, il faut que les couleurs et les lumières en soient un peu exagérées.” Roger de Piles, Cours de peinture par principes (Paris: Jacques Estienne, 1708), 272.

[10] “Si vous vous bornez au matériel, vous tombez dans cette froideur et cette plate propreté qui mettent l’artiste au rang de l’ouvrier, et les tableaux que vous peignez seront ordinairement, ou de couleur de bronze ou d’ivoire.” Louis Tocqué, “Sur la peinture et le portrait,” in Conférences de l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, ed. Jacqueline Lichtenstein and Christian Michel, vol. 5, 6 vols., (Paris: École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, 2012), 454.

[11] On Fleuriau’s multiple petitions for letters of nobility, see Jacques Cauna, Au temps des isles à sucre: histoire d’une plantation de Saint-Domingue au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Karthala, 1987), 48–50.

[12] Brice Martinetti, Les négociants de La Rochelle au XVIIIe siècle (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2013), 287–327.

[13] Ibid., 299. On the decoration of the hôtel Fleuriau, see also Cauna, Au temps des isles à sucre, 51.

[14] Gabriel-François Coyer, La Noblesse Commerçante (London: Duchesne, 1756), 125.

[15] Paul Romain Chaperon, Traité de la peinture au pastel (Paris: Defer de Maisonneuve, 1788), 121.

Cite this post as: Oliver Wunsch, “Fleuriau’s Skin,” Colonial Networks (July 2025), https://www.colonialnetworks.org/?p=849.