Arielle Xena Alterwaite (Brown University)

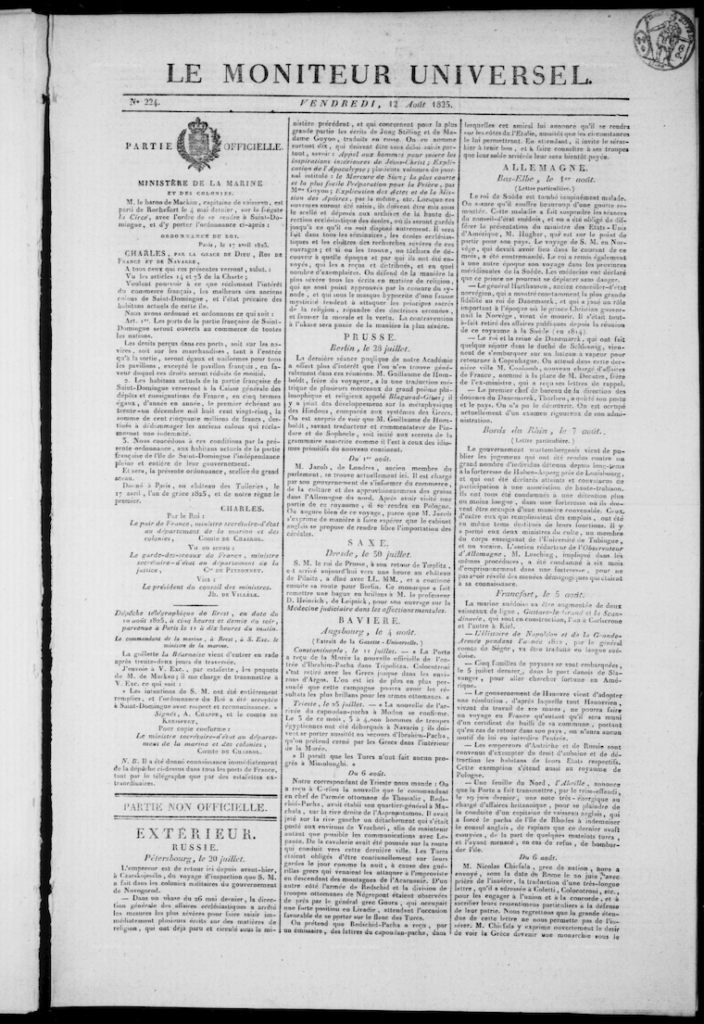

On June 26, 1826, the French merchant vessel L’Hébé left Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Captained by Mr. Forsans, it contained the purported monetary value of one million Haitian gourdes in coins, carried in 20 chests, each filled with five numbered boxes, totaling 100 boxes.[1] One of these chests (Fig. 1) survives in the museum of the Château de Compiège; it was donated by the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, the French state financial institution charged with the arbitration of Haiti’s sovereign debt. Each of the chest’s boxes was meant to contain 625 “quadruples d’espagne” in Spanish gold, which would form a total estimated sum of 62,500 “quadruples.” This was the amount required to pay the first installment of Haitian debt owed to the French state following the passage of what has since become known as the 1825 Haitian Indemnity.

In 1791, the enslaved and free people of color in the French plantation colony of Saint Domingue rebelled. After the spectacular defeat of French, British, and Spanish troops over the next decade, in 1804, the revolutionaries secured independence, renamed their polity Haiti, and abolished slavery within its borders. Finally, after two decades of diplomatic negotiations and several regime changes within Haiti and France, respectively, Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer and French King Charles X reached an agreement that resulted in the passage of two separate laws, one in France and the other in Haiti.

On the French side, France would gain favorable trading privileges with Haiti, and Haiti would owe former French plantation owners 150 million francs in indemnities due in annual installments (Fig. 2). In exchange, France would recognize the eastern part of the island—the territory that had formerly fallen under French colonial rule—as a sovereign nation, but not the entire island, despite its recent consolidation under Haitian rule.

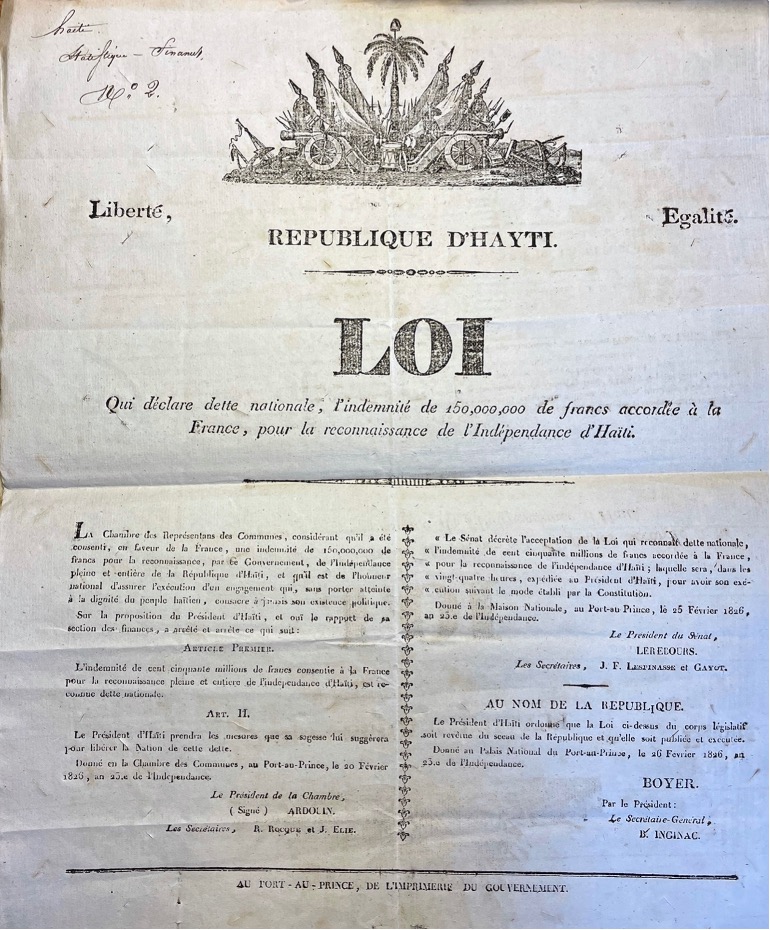

By contrast, in Haiti, the law that established the 1825 Haitian Indemnity looked very different (Fig. 3). It recognized the 150 million francs indemnity as a national debt owed to France, and it passed the Haitian senate without mention of the planters or Haiti’s responsibility to them. It was instead established as a debt between two sovereign entities. Furthermore, no mention was made in Haiti about either the trade deal or the territorial limitations on sovereign recognition established by France—a significant omission, considering that in 1822 Boyer had successfully unified the entire island, including today’s Dominican Republic, under the jurisdiction of the Haitian state.

In addition to the encoded discrepancies between the French and Haitian laws, there were more complications that impacted the payment or nonpayment of Haiti’s debt. For one, the departure of L’Hébé from Port-au-Prince’s harbor did not go as smoothly as French foreign agents anticipated, and Mr. Forsans reported an altercation among Haitians and Frenchmen as the chests were loaded onto the ship. Perhaps the encounter was similar to another Mr. Forsans experienced several months later when he returned to Haiti to engage in commercial transaction. Then, when L’Hébé’s departure passed below Fort Bizoton to the east of Port-au-Prince, Mr. Forsans reported that seven or eight men approached the ship in a “red boat with lavender sails.” Following an hour-long exchange of “the most insulting words,” Haitian sailors, racially identified by Mr. Forsans as both “colored” and “black,” allowed L’Hébé to depart with the coin-stuffed chests that had been filled at the Haitian treasury.[2] And although their names and voices remain absent from the fraught historical record, we nonetheless have a glimpse at the real threat that their actions posed to shipment of money and goods in the name of indemnity payments.

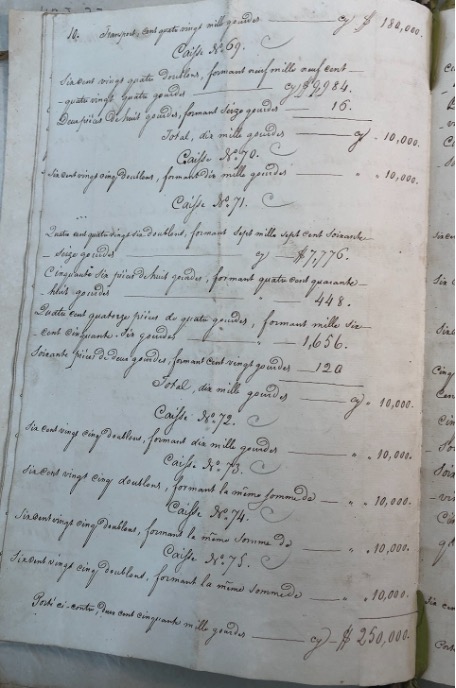

There were still further material realities that threatened to undermine the French extraction of specie payments from Haiti in practice. Although chests like the one pictured above were supposed to contain a set sum in the currency of the franc (France’s national currency, which was pegged to gold and silver), the Haitian government had valued the sum in its own national currency, the gourde. At the same time, despite France’s efforts to establish the franc as an international standard during an era of many global currencies, Haitian authorities often filled the payment chests with a variety of coins, not solely French francs. For example, in the first installment shipment, 34,551 gourdes of the total million were paid out specifically in Haitian-minted coins, rather than French specie. French officials, tasked with verifying and sorting these mixed payments, kept meticulous records of the different coins received—an act documented in their official tallies (Fig. 4). In so doing, these officials bolstered France’s efforts to standardize payments solely in the monies of the lender. In today’s terms, this is precisely what economists Barry Eichengreen and Ricardo Hausmann refer to as the problem of “original sin,” in which a sovereign nation is unable to borrow abroad in its own national currency, resulting in an external debt denominated in foreign currency that exposes the developing nation to exchange rate risk and financial fragility.[3] We might, therefore, argue that the monetary form Haiti’s sovereign debt took constituted an early experiment in a practice that would pervasively expand to impoverish nations in the Global South.

Yet Haiti’s metallic messiness was not merely arbitrary. It signaled Haitian actors’ attempt to exercise some agency over how the debt would be paid and to resist French demands. French officials, meanwhile, readily attempted to sabotage the Haitian state’s monetary sovereignty by undervaluing Haitian specie shipments. For example, although this first payment of the indemnity was meant to be equivalent to six million francs, upon arrival in France, the specie was valued by French officials at a mere 5,300,000 francs. The French state further discredited Haitian coins, noting they lacked sufficient metal content to be of equivalent value to other European currencies.

On the surface, the problem of Haitian coins was repositioned as an issue of international monetary standards, but at the same time, it served as a means through which France could impose structural barriers to Haitian autonomy. When Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer came to power in 1818, he issued a new coinage featuring his effigy, based on a weighted system (with each gourde weighing “50 grains,” the half-piece escalin “25 grains,” and the quarter trois sous “12 ½ grains”). Yet according to a French consular report from October 30, 1826, French officials claimed that the Haitian government had gathered “all the materials of money which one could find, & in particular all the Spanish species which existed in the various coffers of the State and put them in the furnace with unspecified proportions of other metals.” Copper, brass, tin, zinc, and lead were all used as alloys, resulting in coins that, again according to the French, contained only a quarter and sometimes as little as a fifth of gold or silver. Furthermore, the French consuls claimed, “various materials were thrown into molds” without being weighed separately, resulting in different metal values for coins minted “from one day to the next”[4] (Fig. 5).

Over and above French officials’ squabbles, the symbolism of the coins minted in Port-au-Prince both synthesized and challenged Western monetary ideas, showing material faces that represent the crux of modern financial imperialism. For example, in 1813, Haitian President Alexandre Pétion issued the minting of new silver coins in denominations of 6, 12, and 25 centimes. They bore the Haitian palm tree of liberty topped with a French revolutionary Phrygian cap on one side, and a serpent biting its tail on the other. Historian Johnhenry Gonzalez has argued that the snake represented the Dahomey and Vodou deity Damballah Wedo, or the creator. In his words, these “unique coins are the first and only New World currency to feature the image of an African deity.” [5]

The very existence of these coins symbolized a profound transformation: in a society where slavery had once forbidden the enslaved from handling money, the ability to mint and circulate national currency now marked the political change brought by emancipation, making it possible for formerly enslaved people to participate in commercial life as economic actors. Although it is difficult to definitely say whether the symbolism was, in fact, perceived by many Haitians as such, in the wording of the official law, the serpent consuming its own tail was meant to be interpreted as an “emblem of prudence,” avoiding any official mention of anything that might approximate vodou epistemology.[6] Still, by 1828, Boyer ordered the snake coins to be removed from circulation, replacing their effigy with his own, effectively effacing the potentially spiritually potent token with a classically Western motif.[7] While the placement of Boyer’s profile now parroted the design of European coins like the franc (which displayed the portrait of Charles X on one side, and the House of Bourbon’s coat of arms on the other), Haitian resilience nonetheless persisted in the national insignia—threatening canon fire—and in the very fact of their domestic minting and global circulation.

Even if fixing the metal content of Haitian gourdes were possible, and even if specific expressions of Haitian symbolism were removed from its coinage, foreign powers continually cast Haiti as a place plagued by counterfeit coins. There were “immense quantities of false gourdes being made in the United States, mainly in New York,” one report claimed, “where they are sold publicly and in various price ranges.” False coins were supposedly also minted in Glasgow, Scotland, and, in both cases, “the introducers take care to make an assortment of the various false types, to which they mix good ones, a necessary precaution to deceive more surely the farmer, who, in spite of his ignorance, would be suspicious at the appearance of a certain number of entirely similar pieces.” As a result, false money circulated less among merchants in commercial ports, but was traded directly with Haitian coffee producers in “the houses of the interior.”[8]

Although French officials devalued Haiti’s material payments, this did not stop the sale and liquidation of what Haiti did ship within the French state. In subsequent years, the Haitian state sent still more assorted metals and even commodities like coffee to make payments on the indemnity. Just a few months after the initial specie-only shipment brought to France on L’Hébé, the Haitian government used its own recently purchased ship L’Haïtien, loaded with “old copper,” coffee, cotton, and dyewood, for the second payment bound for Le Havre, only to be denied by the French government as a full means of payment.[9] But in the event that the Haitian government did send chests of coins, when these monies arrived in Paris, they would be offered up for sale at a public auction by posters (see Fig. 6 for a surviving example, albeit from the 1840s) so that they could be sold to private bankers in exchange for French francs.

Only once the conversion took place could francs purchased on behalf of the Haitian government be deposited in the Caisse des dépôts et consignations. The francs would be held by the Caisse until, in every case, a former French plantation owner and his or her descendants were deemed eligible by a French government commission to apply for an indemnity payment. They would only receive the portions of the total amount in annual instalments, subject to when Haitian chests filled with coins again arrived in France. Ultimately, the form of Haiti’s debt payments mattered greatly in the first half of the nineteenth century. The materials of money—the actual coins, metals, and even goods sent from Haiti to France—played a crucial role in shaping both the immediate and long-term valuation of the 1825 Haitian indemnity. As detailed in The New York Times, the 1825 Haitian indemnity, initially set at 150 million francs (roughly $600 million today), was not simply a number, but a sum that, compounded over time, could have added over $21 billion to Haiti’s economy.[10] Debt payments were never simple, and their real value fluctuated with the physical currency and commodities used for payment, the variability in metal content, and the contested legitimacy of Haitian coinage. As legal historian Malick Ghachem emphasizes, the indemnity’s actual cost was not only financial but also a blow to Haiti’s monetary sovereignty—the nation’s ability to control its own currency and financial system without external interference.[11] By forcing Haiti to pay in forms dictated and devalued by foreign powers, France used the 1825 Indemnity to extract gold and silver and to entrench a system where Haiti’s economic fate was dictated from abroad with every chest that crossed the Atlantic.

[1] Archives Départementales des Landes, France, 49J73, “Procès Verbal,” June 1826.

[2] Letter from Mr. Forsans cited in Thomas Madiou, Histoire d’Haïti: Tome VII 1827-1843 (1847; Reprint, Port-au-Prince, Haïti: Editions Henri Deschamps, 1988), 544. On these events, see also François Blancpain, Un siècle de relations financières entre Haïti et al France (1825-1922) (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2001), 66.

[3] Barry Eichengreen and Ricardo Haussmann, “Exchange Rates and Financial Fragility,” National Bureau of Economic Research no. 7418 (November, 1999).

[4] Archives Nationales, Paris, France AE B III 380, Dépêche des Cayes, October 30, 1826.

[5] Johnhenry Gonzalez, Maroon Nation: A History of Revolutionary Haiti (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019), 506.

[6] Linstant Pradine, Recueil general des lois et actes du gouvernement d’Haïti: Tome II (Paris: August Durand, 1860), 168. The significance of the ouroboros has origins in Egypt and is pervasive throughout much of antiquity, but it is true that it is not a prevalent feature of many ancient coinage systems.

[7] Robert Lacombe, “Histoire monétaire de Saint Domingue et de la République d’Haïti, des origins à 1874,” Revue d’histoire des colonies 43, no. 152-153 (1956), 322.

[8] Archives Nationales, Paris, France AE B III 380, Dépêche des Cayes, October 30, 1826.

[9] Centre des Archives diplomatiques du ministère des Affaires étrangères, 248 CCC 1, Port-au-Prince, September 18, 1826.

[10] Catherine Porter, Constant Méheut, Matt Apuzzo, and Selam Gebrekidan, “The Root of Haiti’s Misery: Reparations to Enslavers,” The New York Times, May 20, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/20/world/americas/haiti-history-colonized-france.html (all web links accessed August 4, 2025).

[11] Malick Ghachem, “The Real Intervention Haiti Needs,” Foreign Policy, September 14, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/09/14/haiti-crisis-intervention-gangs-colonialism-france-us-history-monetary-policy/.

Cite this post as: Arielle Xena Alterwaite, “The Many Monies of the 1825 Haitian Indemnity,” Colonial Networks (August 2025), https://www.colonialnetworks.org/?p=882.