Amanda Maffei (Università degli Studi di Milano and Institut Catholique de Paris)

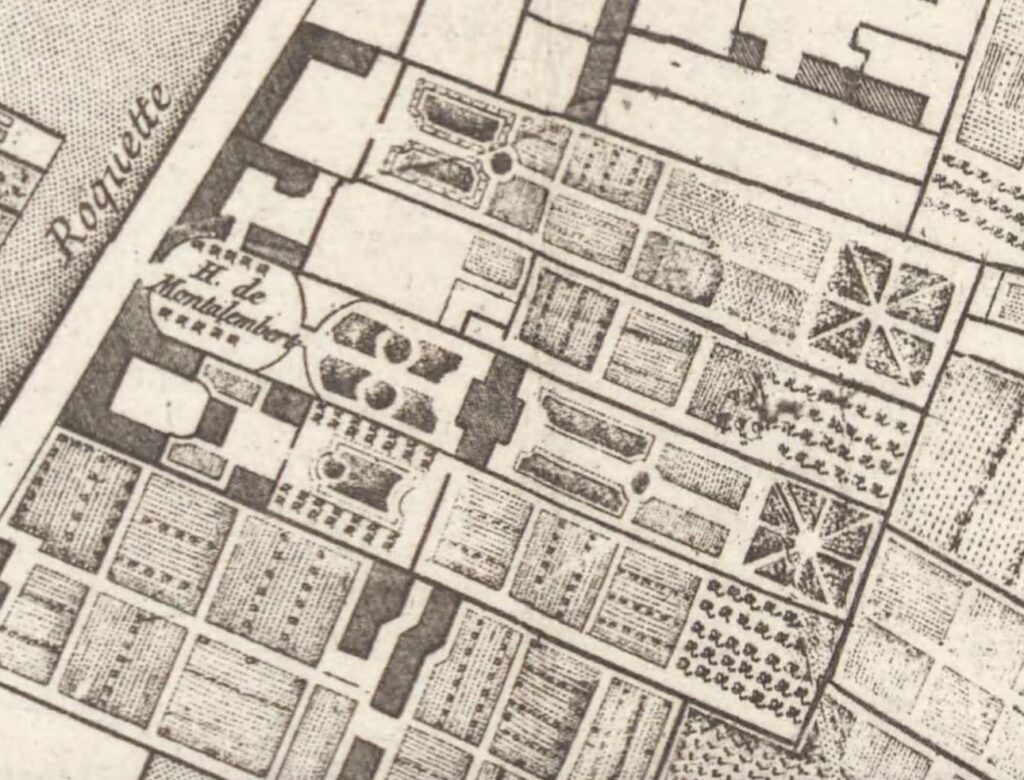

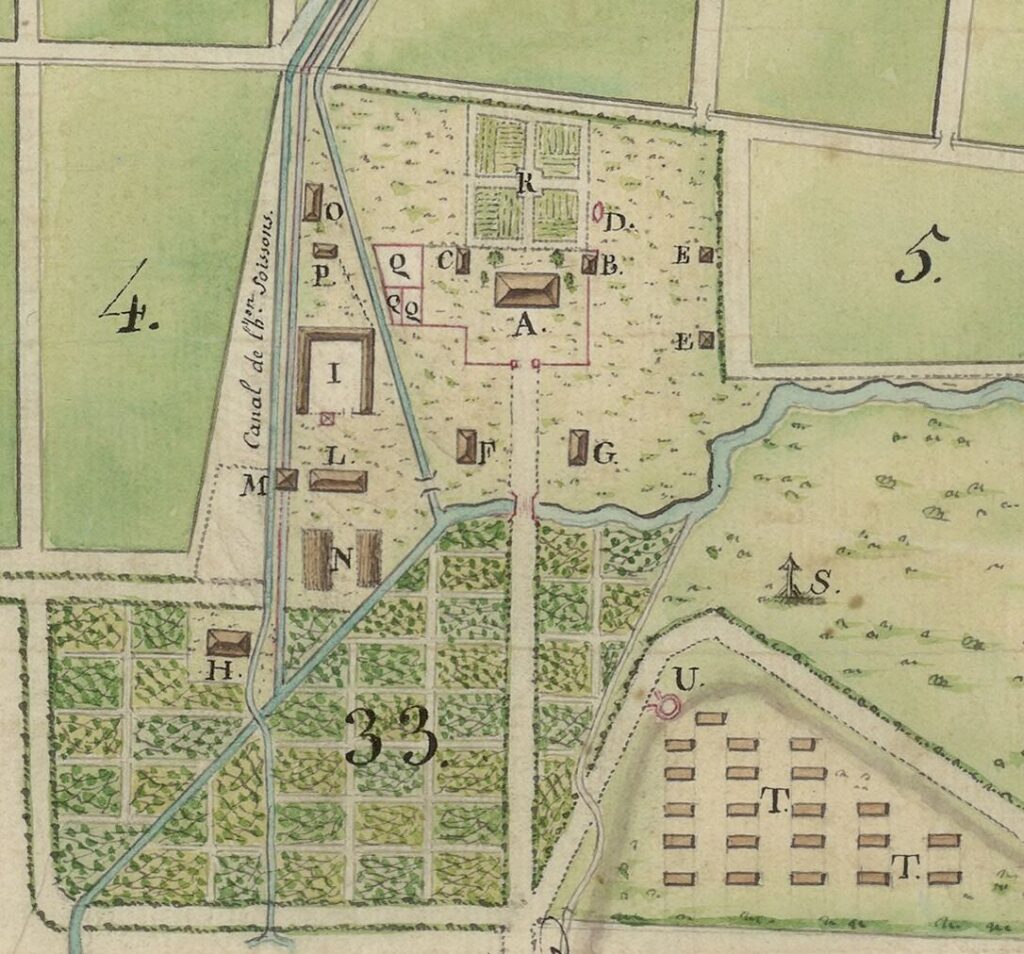

Maps and other images associated with the family of Jean-Charles and Marc-René de Montalembert offer an unusually clear window onto the visual culture that connected Enlightenment Paris and colonial Saint-Domingue in the final decades of the eighteenth century.[1] At once noble, technical, and deeply visual, the Montalembert family inhabited two worlds: an hôtel particulier in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and a series of plantations in the fertile Cul-de-Sac plain near Port-au-Prince. The forms of these distant properties mirrored one another with striking precision (Figs. 1 and 2).[2] Their story reveals how a single aesthetic language, built on geometry, symmetry, and the authority of the eye, could travel across the Atlantic, shaping both metropolitan and colonial environments before unraveling in the age of revolutions.[3]

A Family of Two Worlds

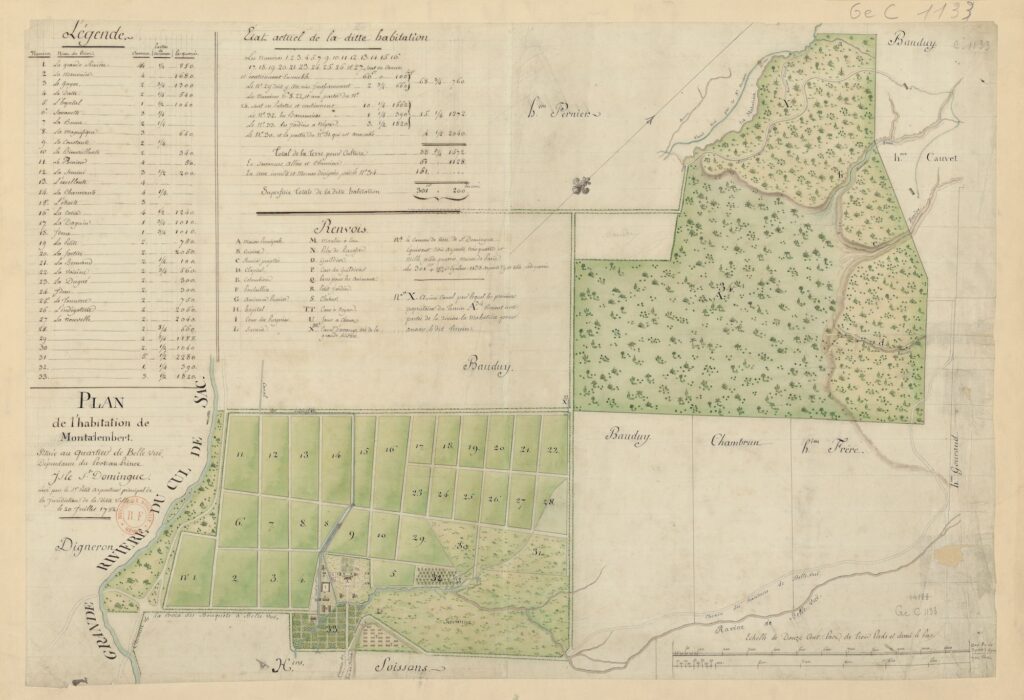

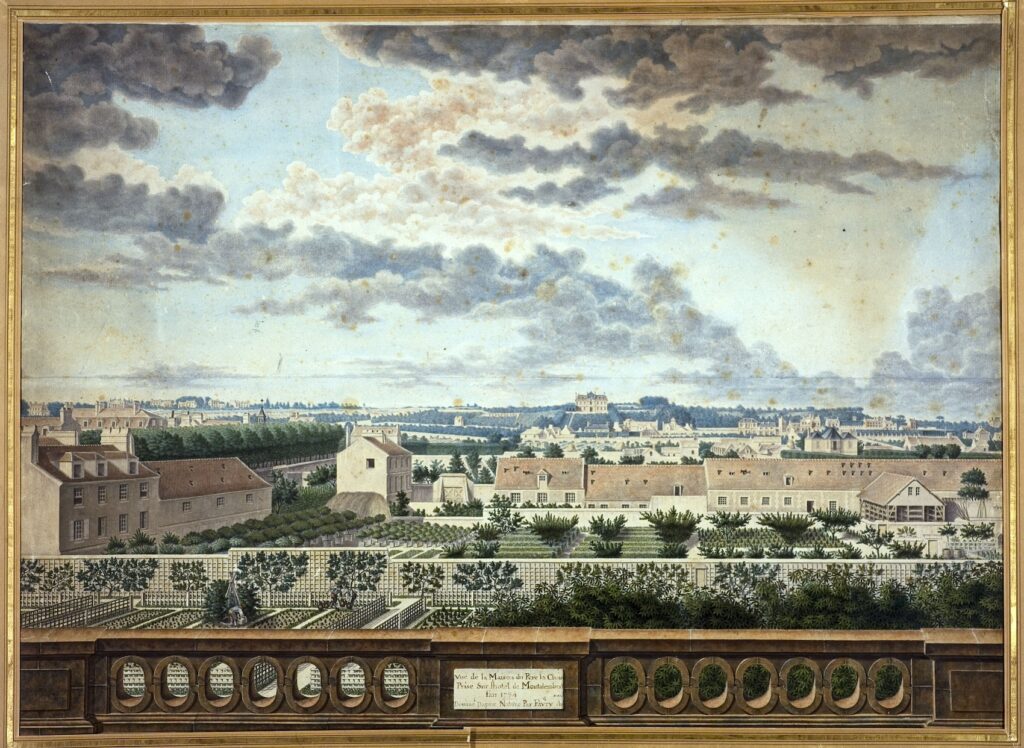

Marc-René de Montalembert, a military engineer and theorist of fortifications, and his nephew Jean-Charles, an officer of the marine infantry, belonged to an aristocracy that redefined itself through colonial investment. By the 1780s, the family managed large sugar estates in Saint-Domingue through detailed maps, correspondence, and the work of professional surveyors.[4] Their Paris house, meanwhile, stood as an emblem of rational domestic order: a symmetrical façade, a circular vestibule, and a formal garden extending toward the present location of Père-Lachaise. This architectural composition found its echo overseas. Both house and plantation expressed the same visual ideal: an ordered space conceived to be seen, measured, and owned (Fig. 3).[5]

For the Montalemberts, vision was a social instrument. It organized the family’s identity as both engineers and proprietors, bridging the realms of art and administration. Their material and visual culture—drawings, models, paintings, and decorative objects—shaped a coherent system of representation that renders the exercise of power as an aesthetic act.

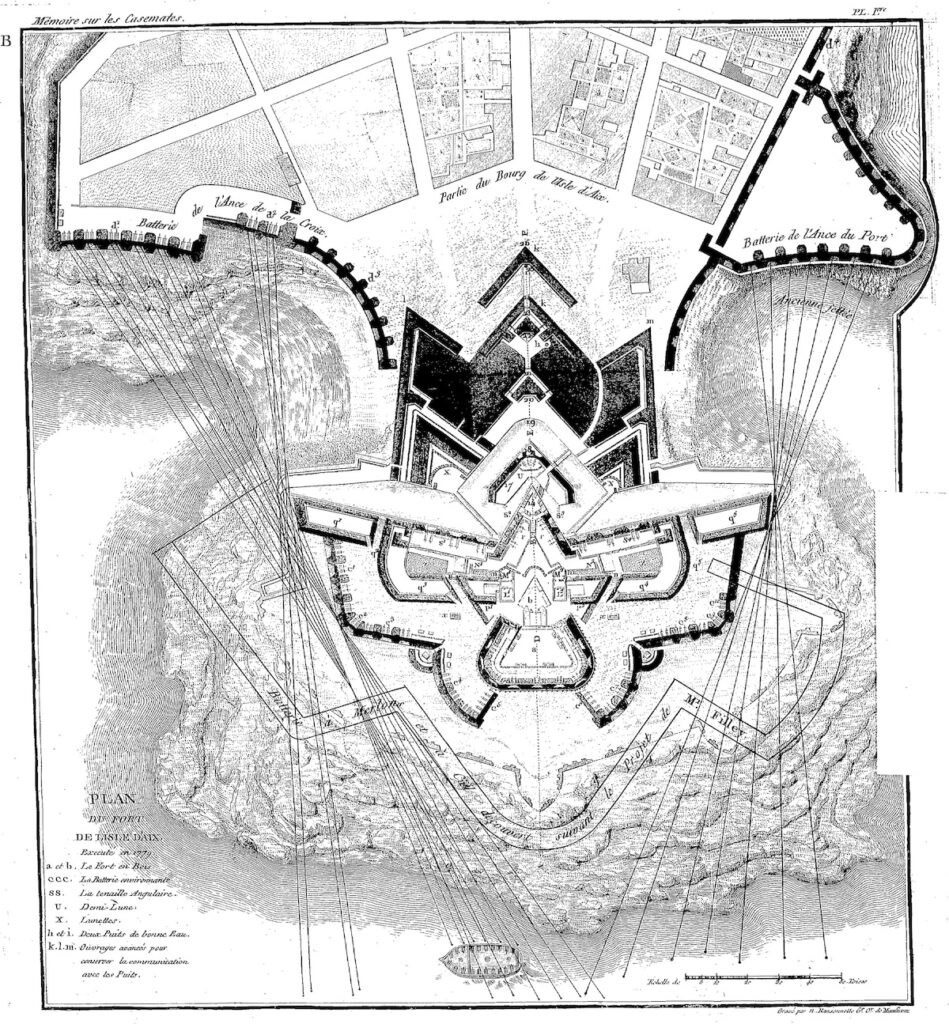

The Aesthetic of Measurement

The Montalemberts’ world was shaped by what might be called an aesthetic of measurement: a belief that beauty and reason shared the same geometrical foundation. Marc-René’s cabinet de fortifications, installed in the family’s Paris residence, assembled more than a hundred plans-reliefs and mechanical devices illustrating his theories of “perpendicular fortification.” These intricate models—part scientific apparatus, part visual theater—transformed the art of war into a spectacle of precision (Fig. 4).[6]

Jean-Charles extended this logic to the Caribbean landscape. His plantations in the Savane du Blond were surveyed by the royal engineers Petit and Sonis in 1782 and 1791, producing the plans d’habitation now preserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Each map converts the messy reality of labor and terrain into a perfectly legible design: irrigation canals drawn as elegant arabesques, fields distributed in harmonious sequence, and the owner’s house positioned at the compositional center. In these drawings, geometry functions as a visual guarantee of control. The plantation becomes a rational tableau; its human and natural complexities dissolved into the clarity of line.[7]

Art and Possession

This fascination with order extended far beyond engineering. The Montalembert’s artistic world revolved around the same conviction that representation could stabilize reality. In Paris, Jean-Charles and his wife, Marthe-Joséphine de Commarieu, commissioned refined miniatures from Isabey and Jean-Antoine Laurent, while physionotrace engravings by Louis-Gilles Chrétien reproduced their profiles through an early form of mechanical drawing. These portraits, with their precise contours and restrained tonality, materialize the same aesthetic discipline that governed the family’s maps.[8]

Marc-René collected paintings by Claude-Joseph Vernet, whose calm seaports and fortified harbors offered a pictorial parallel to the Montalembert’s geometries of mastery. Vernet’s horizons—half scientific, half theatrical—translated the surveillance of space into art.[9] Around the same time, the watercolor by Du Favry depicting the Hôtel Montalembert and its garden framed the domestic sphere as a perspectival landscape (Fig. 5). The viewer’s gaze moves along the garden axis toward the horizon, as though tracing the invisible line that connects metropolitan order to colonial dominion. Across all these media—maps, portraits, models, paintings, and decorative objects—the act of seeing becomes a form of possession.

The Colonial Image and Its Silences

To examine these works today is to recognize their remarkable coherence and their equally remarkable omissions. The plans d’habitation name the owners but not the workers; they depict irrigation systems but not the enslaved and free Black laborers who built and maintained them.[10] Their apparent transparency rests on the systematic abstraction of human presence. The Montalemberts’ vision of beauty depends on this erasure: the conversion of lived space into diagram. Reading such images through a decolonial lens requires acknowledging what they suppress, and imagining the alternative geographies of subsistence, resistance, and community that unfolded beyond the map’s frame.

Yet even in their silence, these objects provide critical evidence of how aesthetic form operated as a tool of empire. They show how artistic and scientific practices merged in the colonial imagination, and how the language of order became indistinguishable from the language of power.

The Map as a Living Document

The 1791 plan of the habitation Montalembert-Scépeaux, drawn by the royal surveyor Sonis, later acquired an unexpected function. During the upheavals of the Haitian Revolution, the gérant-procureur Louis Jarossay used this very plan to communicate with Jean-Charles de Montalembert, referring to its numbered sections to describe the “state” of the plantation as he envisioned it.[11] Through the grid of the map he narrated, almost day by day, how the estate was being reorganized after the flight of its white owners: fields replanted, irrigation restored, buildings repurposed.

Crucially, Jarossay’s map-based narration does not end with the loss of colonial control. On the contrary, it is precisely after the plantation falls under the authority of military leaders among the free men of color, allied with enslaved workers, that he continues to mobilize the map as an analytical tool, using its grid to register a new, post-control organization of labor and subsistence. This correspondence transforms the map from a symbol of possession into a tool of observation. What was meant to visualize mastery now recorded survival. The steward’s reports claim that free men of color and enslaved laborers worked together to maintain production, establishing a provisional yet coherent order “from below.” In translating these practices into the language of geometry, the map, in his view, inadvertently preserved a glimpse of mutual cooperation and self-organization—traces of a world that colonial imagery, especially during the uprising of Saint-Domingue, aimed to obscure.[12] While most gérants-procureurs described revolt through formulas of “chaos” and “disorder” meant to demonize Black and mixed-race actors, the Montalembert gérant-procureur’s maps-based account imply social and organizational patterns that the conventional rhetoric of panic would normally erase.

Why the Montalemberts Matter

Studying the Montalemberts from an art-historical perspective illuminates the subtle intersections between artistic creation, scientific visualization, and colonial ideology.[13] Their corpus demonstrates that the same visual systems that organized knowledge and space in eighteenth-century France also structured the colonial world overseas. By following their images across media and geography, we can trace how the aesthetics of order functioned as a global technology of power, and how its traces endure in the ways we still value clarity, symmetry, and design.

The Montalemberts remind us that what we call “taste” is never innocent. Their world, suspended between the salon and the plantation, reveals how vision itself became a mode of governance—and how, long after their estates vanished, their images continued to define what was meant to be seen.

[1] There is, to date, no comprehensive study of the Montalembert family; I am currently preparing a full biography. For now, available information relies primarily on the partial biography of Marc-René de Montalembert by Yvon Pierron, Marc-René, marquis de Montalembert (1714-1800). Les illusions perdues (Arléa, 2003).

[2] Information on the Montalembert’s artistic tastes comes from a range of archival and museum collections that are often fragmentary or incomplete. The principal sources include the holdings of the Musée du Louvre, the Musée Carnavalet, the Vernet family papers, the Bibliothèque nationale de France (hereafter BnF), and the Montalembert family’s own private papers.

[3] Geoff Quilley and Dian Kriz, eds., An Economy of Colour: Visual culture and the Atlantic world, 1660-1830 (Manchester University Press, 2003); James A. Delle, The Colonial Caribbean: Landscapes of Power in Jamaica’s Plantation System (Cambridge University Press, 2014); Monica Pretit-Hamard and Philippe Sénéchal, eds., Collections et marché de l’art en France 1789-1848 (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2006); Roberta Panzanelli and Monica Pretit-Hamard, eds., La circulation des oeuvres d’art, 1789-1848 (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2007).

[4] Montalembert family’s private papers; Sonis, Plan de l’habitation appurtenant par indivis à Messire Jean Charles baron de Montalembert, coloniel de cavalerie, 1791, BnF, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53025143x .

[5] For information on the Hôtel Montalembert in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine district of Paris, see Régine de Plinval de Guillebon, “L’ancien hotel Dynoyer, puis Montalembert, Manufacture de porcelain des Frères Darte, rue de la Roquette (11e),” Cahiers de la Rotonde 7 (1984): 19-32.

[6] État des plans en relief qui composent les Cabinets de Fortification de M. le Marquis de Montalembert, à Paris, au mois de Septembre 1783 (Paris, 1783).

[7] Montalembert family’s private papers; Sonis, Plan de l’habitation appurtenant par indivis à Messire Jean Charles baron de Montalembert, 1791, BnF.

[8] René Hennequin, Les portraits au physionotrace gravés de 1788 à 1830: catalogue nominative, biographique et critique illustré des deux premières series (J.-L. Paton, 1932), 82-3.

[9] Léon Lagrange, Joseph Vernet et la peinture au XVIIIe siècle (Paris, Didier, 1864); Charlotte Guichard, “Les écritures ordinaires de Claude-Joseph Vernet: commandes et sociabilité d’un peintre au XVIIIe siècle,” in Jean-Pierre Bardet, Michel Cassan, and François-Joseph Ruggiu, eds., Les écrits du for privé. Object matériels, objets édités (Presses Universitaires de Limoges, 2007), 231-44.

[10] Montalembert family’s private papers; Sonis, Plan de l’habitation appurtenant par indivis à Messire Jean Charles baron de Montalembert, 1791, BnF.

[11] Montalembert family’s private papers, letters from Jarossay dated September-November 1792.

[12] Alejandro E. Gomez, “Images de l’apocalypse des planteurs,” L’Ordinaire des Amériques 215 (2013): http://journals.openedition.org/orda/665 .

[13] James E. McClellan, Colonialism & Science. Saint Domingue in the Old Regime (The University of Chicago Press, 2010).

Cite this post as: Amanda Maffei, “Mapping the Aesthetics of Power: The Montalembert Family between Paris and Saint-Domingue,” Colonial Networks (January 2026), https://www.colonialnetworks.org/?p=930.