Julia Prest (University of St Andrews)

The playhouse most closely associated with the town of Port-au-Prince during the colonial era was built in 1777 and inaugurated with a performance of Martini and Durosoy’s Henri IV, ou la Bataille d’Ivry on 1 January 1778. However, public theatre also existed in Port-au-Prince prior to this date. There is occasional evidence of professional theatrical activity in the 1760s, including newspaper advertisements for performances in 1767 and 1768. On 29 January 1772, the Affiches américaines newspaper announced an upcoming event on 2 February to mark the (re)opening of the local theatre with newly-arrived actors performing Regnard’s Les Folies amoureuses and the opéra-comique, Annette et Lubin (by Favart and Blaise). It is not until 1777 that announcements for upcoming performances in Port-au-Prince become frequent—in the year prior to the opening of the so-called Mesplès playhouse.[1]

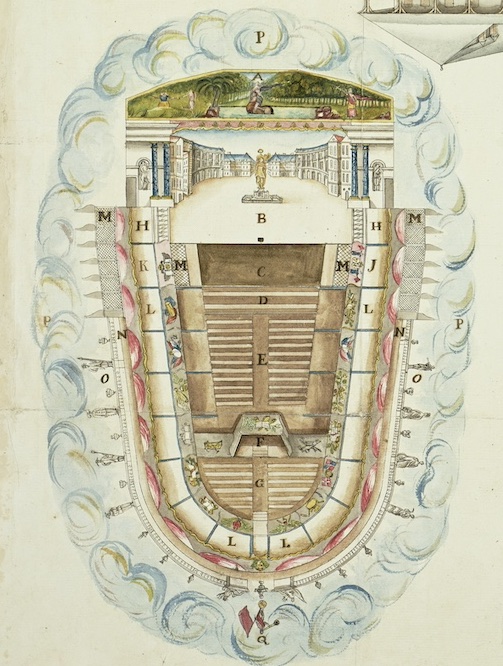

François Mesplès and his associate, Lasserre, were businessmen rather than theatre enthusiasts, and they were persuaded to build a playhouse on the place Vallière in Port-au-Prince because the agreement also involved the construction of a number of other buildings that could be used as businesses or dwellings. A set of detailed architectural drawings showing the place Vallière site (and another at the l’islet de l’Horloge) drawn up after the fact provide valuable information about the design of this wooden playhouse (by contrast, the bigger, grander playhouse in Cap-Français was made of stone). The seating plan features designated seating areas for several groups including colonial administrators and officers from the local garrison. In addition to the ground-level, the theatre had two tiers of boxes.

Of these, fifteen of the second-level boxes at the back and along the side of the playhouse were designated as being “pour les gens de couleur” (for the free people of color). With an average of seven people in each box, the theatre could hold around 105 free people of color, i.e. approximately 14% of its full capacity of around 750 spectators. This policy of segregation, even supposing that it was enforced, does not mean that people from different social groups did not mix at (or en route to) the playhouse in Port-au-Prince. All spectators entered the building via the same narrow entrance, and (white) audience members seated in the first row of boxes used the same staircases as the free people of color who continued up another flight. Indeed, one argument put forward in the 1780s in favor of building a new playhouse was precisely the wish (on the part of some white audience members, at least) to have separate entrances.

What the drawings do not show is any space for enslaved people. While enslaved domestic servants who accompanied their “masters” to the playhouse did not have a designated seating or standing area, they will have spent time in the playhouse’s narrow corridors and even, when summoned, in the boxes themselves. They will sometimes, therefore, have overheard (and even overseen) portions of the works performed. Enslaved people in the playhouses of Saint-Domingue have been called “mitigated spectators”—mitigated because their access to the works was limited and mitigated, above all, because they were not there by choice. Although enslaved people are invisible in the theatre drawings, it is possible that they outnumbered the free people of color present.[2] Also difficult to discern are the diverse contributions made by enslaved people to other aspects of theatre-making. These include the work of assistant painters who helped with the stage sets, that of male and female hairdressers who prepared the actors’ wigs and the seamstresses who sewed and repaired the costumes.[3]

The Port-au-Prince theatre was not always a profitable enterprise, but it enjoyed hundreds of performances of opéras-comiques, comedies and works belonging to other genres from the late 1770s up to mid-November 1791. The Mesplès playhouse was where the local performer of mixed racial ancestry, Minette, made her name singing solo roles in the particularly popular genre of opéra-comique (featuring spoken and sung elements). A (then) enslaved violinist called Julien, who later enjoyed a successful musical career as a free man in France under the name Louis Julien Clarchies, performed a series of duets alongside a white violinist during a theatrical event in Port-au-Prince in 1783. Meanwhile, Mesplès’s long-serving enslaved domestic servant and skilled handyman, Louis, was the go-to person for any minor repairs to his buildings, including the playhouse.

When news of the French Revolution reached Saint-Domingue in September 1789, the editor of the Affiches américaines, Charles Mozard, hastily composed a metatheatrical response called La Répétition interrompue, which is set in the very playhouse in which it was performed on 4 October 1789. The work includes valuable, often satirical, references to theatre-making in that space, including the role of the prompt, and procedures for rehearsing.

The slave revolts near Cap-Français that marked the beginning of the Haitian Revolution took place in August 1791. This led to civil unrest elsewhere in the colony, and in November 1791 a fire in Port-au-Prince destroyed, among other buildings, the Mesplès theatre. During the so-called Haitian revolution, theatrical activity was, unsurprisingly, sporadic at best, but there is evidence of public performances having taken place in Port-au-Prince after 1798 (when the pro-slavery British left the colony) and ongoing in 1802 on another part of the place Vallière. By this time, Saint-Domingue was no longer a slave society but now fighting for its full independence to ensure that this would remain the case.

[1] Details of all performances documented in the local press can be found at https://www.theatreinsaintdomingue.org.

[2] For more on audiences, including “mitigated spectators”, see Julia Prest, Public Theatre and the Enslaved People of Colonial Saint-Domingue (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), chapter 2, pp. 17-50.

[3] For more on these contributions, see Julia Prest, Public Theatre and the Enslaved People of Colonial Saint-Domingue, chapter 5, pp. 153-87.

Cite this post as: Julia Prest, “The Port-au-Prince Playhouse,” Colonial Networks (May 2025), https://www.colonialnetworks.org/?p=796