Julia I. Doe (Columbia University)

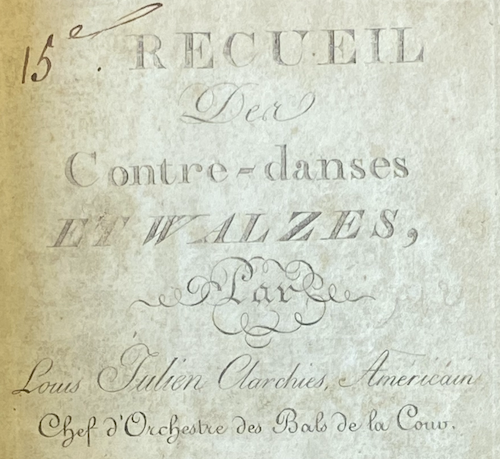

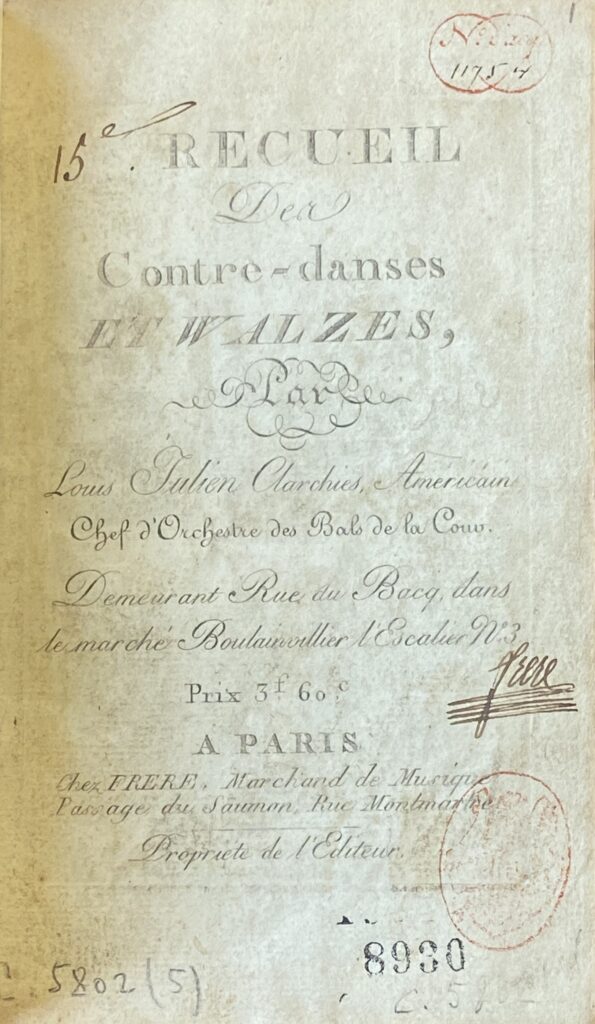

Louis Julien Clarchies was a violinist, composer, and director of dance orchestras who achieved transatlantic fame in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[1] Clarchies was born into slavery in Dutch colonial Curaçao, and first rose to prominence on the public stages of Saint-Domingue. Manumitted on the eve of the Haitian Revolution, he became a key artistic figure at the Napoleonic court, where he was closely associated with the creole empress, Joséphine de Beauharnais.[2] His volumes of published music—comprising several hundred pieces in total—circulated widely both during his lifetime and in the decades after his death (Fig. 1). As one aristocratic observer noted, with only modest hyperbole, Clarchies wrote “the quadrilles that made all of France dance.”[3]

The circumstances of Clarchies’s early life are poorly documented, obscured within a fragmentary and violently asymmetrical set of imperial archives. The musician’s own approximations of his age place his birth between 1766 and 1769.[4] While still a young child, he was trafficked to Saint-Domingue as the attendant of a French ship captain, Louis Frédéric Pichon de Premeslé, sieur de Trémondrie.[5] Across the early modern Caribbean, facility on an instrument factored among the skilled expectations of domestic servitude. On plantations and in urban spaces, enslaved violinists frequently provided music for dancing.[6] In this context, though, Clarchies’s trajectory was remarkable. By his teenage years, he was known as a performer of European concert repertoire. He was a member of the opera orchestra at the Comédie du Cap, and appeared intermittently as a violin and viola soloist at the theater in Port-au-Prince.[7]

Reports from the Affiches américaines indicate that Clarchies was immensely gifted. In 1783, for example, he covered the concertino viola part in Jean-Baptiste Davaux’s C-major symphonie concertante (from the opus 7), appearing alongside two white virtuosos from the metropole.[8] The passagework here is so difficult that the composer added a cautionary note in the score. Davaux writes that the work “was not fashioned for a typical violist,” but should only be executed by a player adept at rapid, violin-style figuration.[9]

As he received accolades as a concert soloist, Clarchies continued to serve a new enslaver—a Crown bureaucrat named Paul Jean-François Le Mercier de la Rivière—as a domestic valet. In this capacity, he made several journeys across the Atlantic in the 1780s.[10] In 1790, this dislocation became permanent.[11] In brief: amidst growing anti-slavery sentiment in the metropole, Mercier de la Rivière traveled to Paris to lobby for the interests of the Saint-Domingue plantocracy.[12] Less than a year into this trip, Mercier de la Rivière died, leaving Clarchies to definitively claim his freedom and rebuild his life in the French capital.[13] He became a citizen when the revolutionary government granted such rights to “every man, regardless of color,” and successfully petitioned for financial compensation as a “refugee” from the colonies.[14] Registering his identification with local authorities in 1793, he described his occupation in a single word: “musician.”[15]

Clarchies seems to have gained a foothold in metropolitan high society by exploiting the networks of his former enslavers. By the late 1790s, he had been hired to perform dance music for the Martinique-born Joséphine, whose family had ties to Mercier de la Rivière through the ancien-régime colonial administration.[16] As other elites clamored to copy her esteemed example, Clarchies became a bona fide Parisian celebrity. Memoirs from the turn of the nineteenth century document the violinist’s presence at salons throughout the capital, entertaining government notables, military officials, nouveaux riches, and members of the reconsolidating aristocracy.[17]

The virtuoso reached yet broader audiences by organizing public dances at the many pleasure gardens that had opened in the aftermath of the Terror. Clarchies’s primary employer was the Elysée-Bourbon (on the grounds of the future Elysée palace). But he also appeared at the Hôtel Mercy, Cercle des Victoires, Hôtel de Longueville, Vauxhall d’Été, Petit Hôtel Montmorency, Théâtre Molière, and Tivoli Gardens, among other sites.[18] In his dispatches from Paris, the Habsburg diplomat Charles de Clary-et-Aldringen described the situation matter-of-factly: “in order for a ball to be truly fashionable, it must showcase Julien.”[19]

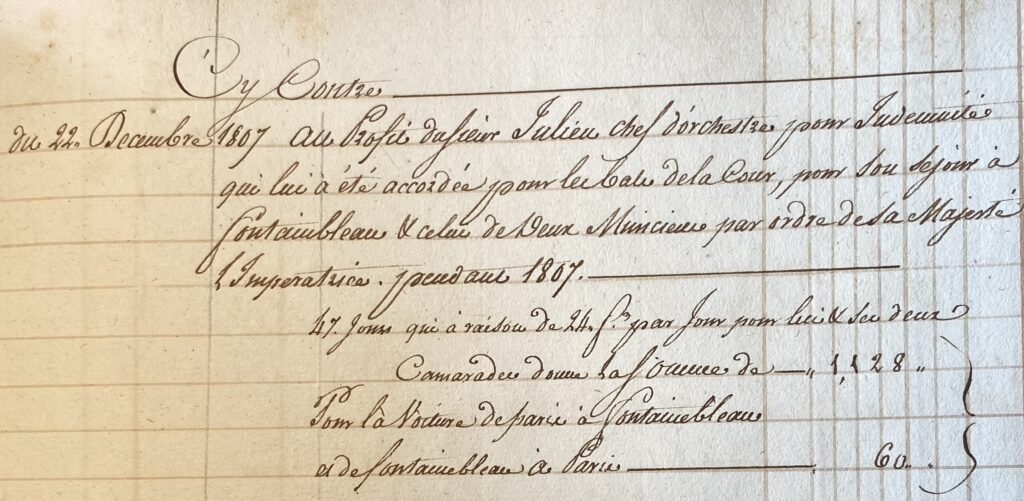

As Clarchies’s engagements proliferated, he remained loyal to his most famous supporter: Joséphine. The violinist followed her to the imperial court upon her husband’s accession as Emperor in 1804. At the outset of the Napoleonic Empire, Clarchies programmed small-scale dances for his patron, a continuation of his role at her private salon (Fig. 2). As in his freelance career, however, the virtuoso’s duties were rapidly expanded, a reflection of both his well-earned reputation and Joséphine’s considerable influence. By 1806 Clarchies was granted the title of chef d’orchestre des bals de la cour. After this juncture, he would become one of the most prominent musical artists in Napoleon’s employ, directing regular state balls while commanding an ensemble of up to three dozen players.[20]

Indeed, one could argue that the violinist’s contributions were more influential than those of his better-known contemporaries (i.e., Rodolphe Kreutzer, the leader of the imperial chapel-orchestra, or Pierre Gardel and Jean-Étienne Despréaux, famed court choreographers) for the way they resonated beyond official sites of government power. Clarchies published extensively after his court appointment, marketing his works through their link to state-sanctioned sociability. In essence, to purchase and perform the violinist’s compositions—“L’Austerlitz,” “La Joséphine,” “La Westphaline,” etc.—was to import imperial festivity into the domestic sphere, a personalization of politics through the enactment of social dance. Eminently adaptable, Clarchies’s final publications (from 1814–15) alluded to the restored Bourbon royals, as extracted in the recording below.

Louis Julien Clarchies, “Quadrille du Duc de Berry,” 25e Recueil des contre-danses et walzes (Paris, 1815).

Clarchies’s musical life reflected the complex and multi-directional mechanisms of artistic transfer between France and the Caribbean in the Age of Revolutions. In his teenage years in Saint-Domingue, the violinist served as an emissary of European concert repertoire. In his adulthood in Paris, his reception was shaped by the biases of his transplanted creole patrons. Despite his manifold performing talents, Clarchies was often perceived as a ménétrier (a minstrel or fiddler) rather than a classical virtuoso—a colonial stereotype of “African” musicianship that became embedded in the metropolitan cultural imagination.

Paul Thiébault, a general in Napoleon’s army, recounted one memorable ball where Clarchies “led his contredanses [from the orchestra] so marvelously that the assembled crowd demanded that he play them again, like a soloist. The greatest violinist in the world could not have presented them as splendidly as he.”[21] Thiébault was unaware of the inadvertent prescience of his statement: Clarchies had, in fact, been a sought-after soloist before circumstances forced him to reorient his career for the Parisian marketplace.

Clarchies’s music circulated long after his death in 1815—both within France and across the vast terrain over which France asserted political dominance. His compositions can be found in manuscript collections from regions of Italy controlled by Napoleon’s Grande Armée;[22] and they were reprinted in Philadelphia, home of many colonial refugees of the Haitian Revolution.[23] They were almost certainly disseminated in New Orleans and in Martinique, sites of vibrant quadrille culture, where they would have been placed back into the fingers of Afro-descendant performers of dance music.

The most important ambassador for Clarchies’s compositions was his son, Isidore Julien Clarchies, who was also a violinist and a leader of dance orchestras. The younger Clarchies had a precarious career, moving frequently in search of work. In the 1830s, he organized spectacles at the Parisian Cirque Olympique; in the 1840s, he directed balls in Bordeaux and in Bilbao, Spain. By the 1850s, he had immigrated to Algeria, which became an official department of France under Napoleon III.[24] Isidore Julien Clarchies brought with him to Africa a repertoire inherited from his father, compiled in the Hexagon but based on a technique forged in the Caribbean. The recursive pattern across this vast distance and longue durée is both striking and sobering: another Napoleonic Empire, another violinist playing dances in its wake.

[1] A longer version of this post appeared in the Spring 2025 newsletter of the Society for Eighteenth Century Music. I am grateful to the society for allowing me to adapt it here.

[2] Pierre Bardin et al., “Julien Clarchies, griffe de Curaçao, affranchi, violoniste et chef d’orchestre des bals de la cour impériale,” Généalogie et histoire de la Caraïbe, 2018, art. 4 (https://www.ghcaraibe.org/articles/2018-art04.pdf).

[3] “Julien, surtout, qui dirigeait les bals de madame Bonaparte, composait alors les quadrilles qui faisaient danser toute la France.” Henri Marie Ghislain de Mérode, Souvenirs du comte de Mérode-Westerloo (Paris: E. Dentu, 1864), 1: 134.

[4] Archives nationales de France, Paris [AN], F/7/4794, “Police générale, Comité de sûreté Générale, Cartes de sûreté délivrées par les comités révolutionnaires des sections du: Finistère et de la Fontaine de Grenelle, 1792/an III,” June 6, 1793; Archives de Paris, 5Mi1 1182, “Extrait du Registre des Actes de décès de l’an 1815,” no. 286, December 26, 1815.

[5] With Trémondrie, Clarchies also traveled to Bordeaux between 1776 and 1778. See Archives départementales de la Gironde, Bordeaux, 6 B 56, folio 88, May 30, 1778; and Érick Noël, ed., Dictionnaire des gens de couleur dans la France moderne (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 2017), 3: 608.

[6] Maria T. N. Ryan, “Hearing Power, Sounding Freedom: Black Practices of Listening, Ear-Training, and Music-Making in the British Colonial Caribbean” (PhD Diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2021), 25–93.

[7] Julia Prest, Public Theatre and the Enslaved People of Saint-Domingue (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 158–61.

[8] Supplement to the Affiches américaines, July 12, 1783, 396.

[9] “Cette partie n’est pas faite pour un Alto ordinaire; elle ne pourra être bien exécutée que par quelqu’un qui aura une grande habitude du Violon.” Jean-Baptiste Davaux, Deux symphonies concertantes, la première pour deux violons principaux et un alto viola- récitans … la seconde pour deux violons principaux, oeuvre VII (Paris: Bailleux, 1773).

[10] Bardin et al., “Julien Clarchies,” 3.

[11] Bardin et al., “Julien Clarchies,” 5; Archives nationales d’outre-mer, Aix-en-Provence [ANOM], COL F5/B/17, 198 (“Liste des passagers & autres qui ont été débarqués en ce Port [Bordeaux], venant des Colonies, pendant le mois de Novembre [1790] sur les Navires ci-après désignés”).

[12] Philippe Haudrère, “Les tribulations de Paul Jean-François Le Mercier de la Rivière, ancien ordonnateur de la Marine, devenu habitant de Saint-Domingue, 1787–1791,” in L’esclave et les plantations de l’établissement de la servitude à son abolition, ed. Philippe Hrodēj (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2009), 187–208.

[13] While a statement of manumission was filed with Parisian notaries in the 1780s (AN, Minutier Central, Étude CXVII, 922, September 4, 1785), Clarchies does not seem to have separated from the household before Mercier de la Rivière’s death. See Bardin et al., “Julien Clarchies,” 5; Archives départementales des Hauts-de-Seine, Registres paroissiaux (Boulogne [paroisse Notre Dame]), “Sépulture de Mr. Paul Jean François le Mercier de la Rivière,” July 9, 1791, E_NUM_BOU_BMS_35 – 1790-1792.

[14] AN, F/15/3376, “Secours aux réfugiés des colonies autres que Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon” (Ci-Coll., dossier 20).

[15] AN, F/7/4794, “Police générale,” June 6, 1793.

[16] Pernille Røge, Economistes and the Reinvention of Empire: France in the Americas and Africa, c. 1750–1802 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 105–52.

[17] Maurice Dupin de Francueil to Marie-Aurore du Saxe, letter of 24 pluviôse an X, in George Sand, Histoire de ma vie (Paris: Michel Lévy Frères, 1856), 3: 99; Mary Berry, Extracts from the Journals and Correspondence of Miss Berry from the Year 1783 to 1852, ed. Lady Theresa Lewis, 2nd edition (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1866), 2: 174; Paul Thiébault, Mémoires du Général Bon. Thiébault (Paris: Librairie Plon, 1894), 3: 271; J. de Norvins, Souvenirs d’un historien de Napoléon (Paris: Librarie Plon, 1896), 2: 288; A. Laquiante, Un hiver à Paris sous le Consulat, 1802–1803, d’après les lettres de J.-F. Reichardt (Paris: Librairie Plon, 1896), 100–1.

[18] Berry, Extracts from the Journals and Correspondence, 2: 178; Journal de Paris, 24 nîvose an IX, 694; Journal de Paris, 7 ventôse an 9, 950; Journal de Paris, 23 frimaire an IX, 506; Journal des débats, 14 brumaire an X, 2; Journal des débats, 17 frimaire an XII, 2; Journal de Paris, 24 pluviôse an IX, 872.

[19] “Pour qu’un bal soit fashionable, il faut y avoir Julien.” Charles de Clary-et-Aldringen, Souvenirs du Prince Charles de Clary-et-Aldringen: Trois mois à Paris lors du marriage de l’empereur Napoléon I et l’archiduchesse Marie-Louise (Paris: Librairie Plon, 1914), 233.

[20] AN, O/2/25–O/2/65b, “Intendance générale de la Maison de l’Empereur.”

[21] Julien “jouait la contredanse si merveilleusement qu’on lui demandait de la jouer en soliste, et que le Premier violon du monde ne l’aurait pas mieux jouée que lui.” Thiébault, Mémoires du Général Bon. Thiébault, 3: 271.

[22] Susan Parisi, ed., The music library of a noble Florentine family: a catalogue raisonné of manuscripts and prints of the 1720s to the 1850s collected by the Ricasoli Family now housed in the University of Louisville Music Library (Sterling Heights, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 2012); Cornelis Vanistendael, “Shaping Europe’s First Dance Craze—The Role of Napoleon’s Grande Armée in the dissemination of the Quadrille (1795–1815),” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 36, no. 1 (2018): 91–111.

[23] William B. Crandell, Cotillons & Waltzes Selected for the Cotillion Balls, Adapted for the Piano Forte (Philadelphia: G. Willig, 1815).

[24] Bardin et al., “Julien Clarchies,” 8; ANOM, État Civil (Algérie ALGER 1853), “Acte de décès,” September 10, 1853, 273.

Cite this post as: Julia I. Doe, “Louis Julien Clarchies, c. 1767-1815: A Transatlantic Musical Legacy,” Colonial Networks (July 2025), https://www.colonialnetworks.org/?p=869