Mary Pedley (William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan)

The map entitled Plan de la plaine du Cap François en l’Isle St. Domingue is a fascinating example of cartographic composition and engraving skill (Fig. 1). It combines the measured detail of property surveys, the shaded values of topographical depiction, the soundings and nautical codes of a marine chart, and the presentation attributes of the print world in its ornate dedication and title cartouches and decorative frame. The seductive beauty of the map lies in aesthetic qualities that reinforce a claim to veracity and even accuracy. To assess such a claim, we must ask the basic questions of a primary source: who made it, where and when, by what method, for whom, and for what purpose.

Reading the Map

The Plan de la Plaine du Cap françois is a large map, nearly 82 by 104 cm (2 ½ by 3 feet). It was published in two versions, one printed within an engraved decorative frame, and one printed without the frame, or trimmed very closely.[1] A trompe l’oeil cartouche in the top right displays the title on a draped curtain supported by monkeys on either side; two additional monkeys join snakes slithering up the supports, and two allegorical female figures recline in the shade of a parasol. The full title reads: Plan de la Plaine du Cap françois en l’Isle St. Domingue, Rédigé d’après les dernières Opérations Geometriques Des Ingénieurs du Roy Par René Phelipeau, Ingénieur Géographe A Paris 1786. (Plan of the plain of Cap Français on the island of Saint Domingue, edited according to the latest geometrical operations of the engineers of the King by René Phelipeau, Geographical Engineer, at Paris 1786.) A further ornate cartouche at the bottom left, comprising a coronet and coat of arms flanked by nude winged figures, frames the dedication to the comte de Vaudreuil, that is, Joseph Hyacinthe François de Paule de Rigaud (1740–1817), a Paris-based courtier and art collector whose father had been the colonial governor of Saint Domingue.

The bottom left corner also includes the letters A.P.D.R. (Avec Privilege du Roi), indicating royal copyright protection, and underneath that is “Rue St Jacques No. 45,” Phelipeau’s Paris address, implying that the map could be acquired there.[2] At the center bottom the scale is indicated: approximately 1:28,000, which is a standard military map scale of the period (ca. 2 ½ inches to a mile). The geodetic coordinates of Cap François are given in the margins: “Longitude Occidentale 74d 38m 25s du Meridien de Paris,” and “Le Cap a l’Eglise 19d 46m 24d Latitude Nord.” A compass above the scale bar shows us that the map is oriented to the south; thus north is at the bottom of the map.

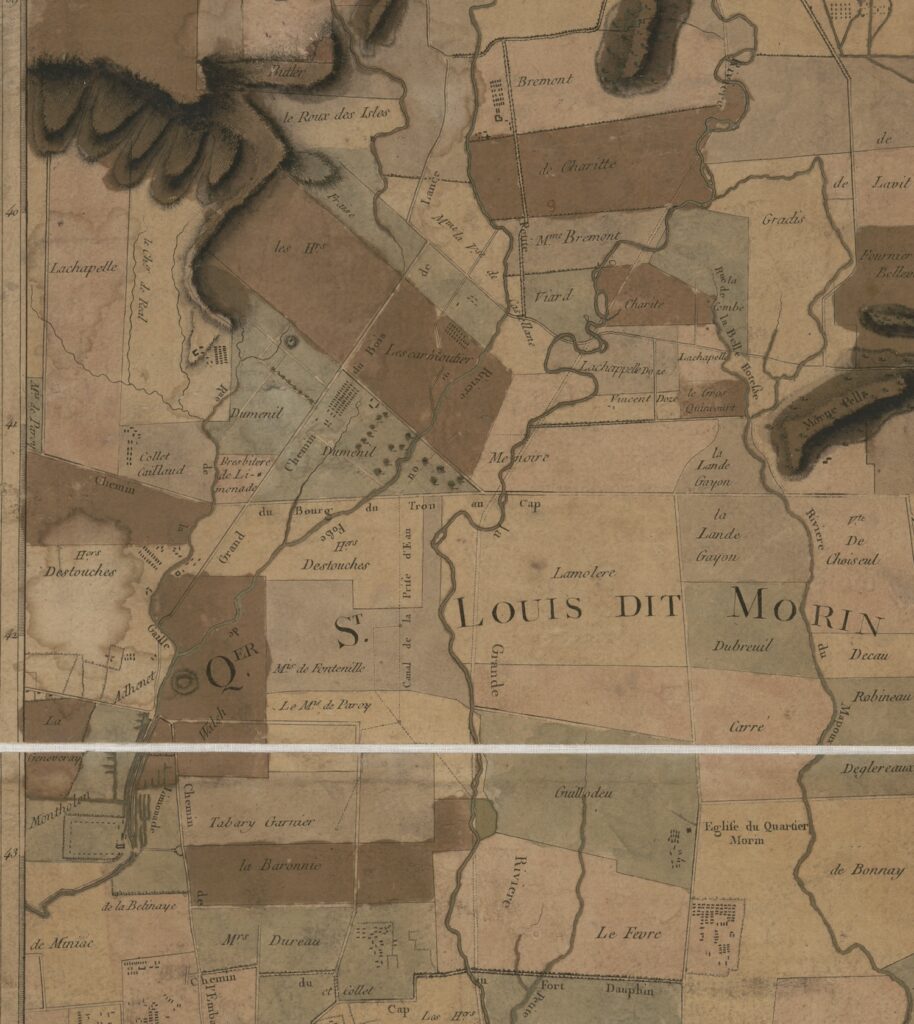

The contents of the map depict three layers of information about the space around the city of Cap François: first, the land as physical space of mountain, plain, rivers, and watersheds, with the sea marking its coastline; second, the land as property bounded and claimed by named proprietors; and third, the city’s place on the globe, determined by its coordinates of longitude and latitude. The mapmaking techniques of lines, dots, numbers, words, and symbols render these layers visible. The manual addition of color after printing further clarifies the content. For example, the sea is differentiated from land in two ways: soundings (numbers representing depths, usually in fathoms or six feet) are placed in the bay of Cap François and to the east near the Bourg de l’Embarcadère de Limonade; dotted lines outline the shoals of both the bay of Cap François and the bay further to the west of Acul. A pale green was added to all copies so far observed to outline the coast.

On land, line work assumes a different function. Dotted straight lines show the boundaries of property ownership of the habitations (plantations), most probably of sugar production, a product implied rather than shown. At higher elevations, coffee would have been cultivated. On some habitations, dots and squares represent the main house, outbuildings, and quarters for enslaved workers, representations that could be specific to a particular habitation or generic, as most sugar plantations followed a standard arrangement of structures to increase productivity (Fig. 2). Words provide the names of putative owners. Ongoing research for this project aims to determine whether these were in fact the owners in 1786, the date of the map, or whether a habitation name reflects a former owner or serves as a place name. Social status is shown by an owner’s title (e.g. le Cmt de Vaudreuil, Le Mqs de Paroy, Cte de Raynaud de Villevert, Chr de Lacombe); gender may be noted (e.g. Mme Bremont, Mme la Vi[comtess]e de Castellane, Vve Blanfossé); and the status of a free person of color of either gender by the designation of “n.l.” for “négre libre” or “négresse libre” (e.g., Nicolas n.l., Rose n.l.)

Hachures (short engraved lines) are used to show elevation of the physical landscape: lines that are closer together depict steeper slopes, creating a shaded effect in engraved printing. If watercolor is added, it emphasizes the shading. Summits, which appear white, are left free from linework to emphasize the height. Rivers and creeks are engraved with sinuous lines—parallel lines for larger rivers, and single lighter lines for smaller creeks and rivulets. A variety of parallel lines differentiate properties: some are unbroken, some are dotted, some are a thicker line paired with a lighter line. As there is no key, we can surmise that these may not only show property boundaries but also irrigation ditches or canals, a vital part of sugar production, and a shared investment by property owners.

The Author

René Phelipeau (1752 – ?) signs himself as “ingénieur géographe” in the title and as “géographe” in his dedication to Vaudreuil. In neither case does he append “du roi” to this style, so he was not a member of the ingénieurs-géographes du roi (geographical engineers of the king), who belonged to a specialized corps that were subsidized by the royal purse from the time of Louis XIV, and whose charge was to create topographical maps of military and strategic importance for the King and his army.[3] As an independent geographer or engineer or both, he was either self-taught or instructed by an elder who trained him in design and presentation, measuring and scale.

Whether Phelipeau ever worked in Saint Domingue is a mystery. A specialized group of ingénieurs géographes were sent to the island in the 1760s to perform large scale topographical surveys on orders from the ministry of the Marine, the department of state responsible for overseas colonies.[4] Phelipeau’s name is not among them, nor is it among the engineers responsible for fortifications and infrastructure on the island. Nor is he mentioned as a local surveyor (arpenteur), who performed property surveys of individual habitations or localities, surveys used in property sales, lawsuits, inheritances, and other legal situations.

Context of the Map’s Production

Phelipeau’s career as a mapmaker is uneven, with very few maps attributed to him prior to the outpouring of Saint Domingue maps: seventeen engraved and printed maps of the colony produced between 1785 and 1790. Five of these are large wall maps, all similar in size, style, and scale to four other maps, measuring ca. 80-90 by 60-90 cm, printed from two plates, showing the topography of the environs and any towns in plan.[5] Four of the five are dedicated to titled persons who either held government office or were major landholders on the island: Plan de la ville du Cap Français et de ses environs : avec ses augmentations et changements projettés, 1785, dedicated to the maréchal de Castries, minister of state and the Marine;[6] Plan de la plaine du Cap François en l’Isle St. Domingue, 1786, dedicated to Vaudreuil; Plan de la plaine du fond de l’Isle à Vache de l’Isle St Domingue, 1786 (no dedication); Plan de la ville des Cayes, dans l’Isle Saint-Domingue, 1786, dedicated to César Henri, comte de la Luzerne, governor general of the Leeward Islands (sous le vent); Plan du quartier de l’Artibonite, Isle St. Domingue; refermant les paroisses de St. Marc, de la Petite Rivière et des Verettes, 1790, dedicated to the comte d’Agoult, chevalier du l’ordre de St Louis, St Lazare. Each of these maps was printed within the same decorative frame, suitable for hanging on a wall. Some copies survive with the frame trimmed, allowing for dissection and pasting onto a linen backing, which allows the map to be folded and stored in a case, suitable for carrying.

In addition to Phelipeau’s large wall maps are twelve printed smaller plans of port cities in Saint Domingue, which were available separately (each has an address in Paris) or gathered into the Recueil de vues des lieux principaux de la Colonie Françoise de Saint-Domingue, gravées par les soins de M. Ponce, accompagnées de cartes et plans de la même colonie, gravés par les soins de M. Phelipeau….. Paris, 1791. (Fig 3). They are similar in size, scope, style, and content. Dated 1785 are plans of Leogane, Port au Prince, and Saint Marc. Dated 1786 are Tiberon[7], Petit Goave, St Louis, Mole St. Nicolas, Jacmel, Fort Dauphin, Les Cayes, Port de Paix, and a smaller version of Cap François. They measure between 40-45 cm high by 26-36 cm wide; the plan of Cap François is slightly larger than the rest at 60 x 44 cm. Each shows the topography of the environs with habitations and owners, the layout of the town in plan, the soundings in the harbor, if known, a compass to show orientation, a consistent scale in units of toises, and the precise longitude and latitude of each place. Coloring is sometimes added, at the discretion of the owner or upon the instruction of the seller, but on extant copies a distinct consistency and similarity of colors and shades suggest that Phelipeau may have supervised the coloring.

The Map’s Sources and Publisher

The title of the Plan de la plaine de la ville du Cap tells us that the map was “compiled based on the latest geometric observations of the royal engineers.”On the face of it this would refer to the (unfinished) topographical survey performed in the 1760s by the ingénieurs-géographes du roi, or even more recent surveys by resident engineers. How did Phelipeau have access to these maps, if he was not present in Saint Domingue? The answer may lie with Médéric-Louis-Élie Moreau de Saint Méry (1750-1819), a Creole lawyer, publisher, and politician, who spent much of his life living in and writing about Saint Domingue. Phelipeau is listed as one of the publishers of the Receuil des vues, along with the engraver Nicolas Ponce (1746-1831) and Moreau de Saint Méry. The Receuil was designed to accompany the latter’s six volume work, the Loix et constitutions des colonies françoises de l’Amérique sous le Vent, published between 1784 and 1790 (the same period in which Phélipeau’s maps of Saint Domingue were printed). Moreau de Saint-Méry’s dense work comprised transcriptions of laws and ordonnances from both the government in France and locally on Saint Domingue, arranged in chronological order from 1550 to 1785, covering a wide range of topics and situations. The Discours Préliminaire, found in the first volume, outlines the author’s goals of wishing to understand the current legal structure of the colony in order to improve it and to provide for fellow lawyers like himself a law code of statutes already on the books. Moreau de Saint Méry closes the Discours by thanking those who helped make the voluminous work possible, including M. Dumesnil, the surveyor at Plaisance; M. Rabié, colonel in the Infantry and Engineer in Chief at Cap François; Hesse, Sorel, and Moreau, ordinary engineers; and M. Pinard de la Roziere, principal surveyor at Saint Marc. “They have furnished me with the greater part of the plans of places and public monuments of Saint Domingue which form, with the general map of the island, the engraving of the Historic part [of this work].”[8]

René-Gabriel Rabié, Charles-François Hesse, Antoine-François Sorrel, and Jean-Baptiste Moreau were engineer-geographers on Saint Domingue.[9] Sorrel and Moreau participated in the topographical surveys of 1763-69; Hesse arrived later. The topographical survey work of all these engineers would have served Phelipeau well in his compilation of the plans of towns and environs. The sources for the marine soundings and geodetic coordinates of longitude and latitude could have come from the work of naval officer-scientists Claret de Fleurieu, Verdun de la Crenne, and Chastenet, comte de Puységur, who traveled on separate voyages to the Antilles between 1768 and 1785 to test the chronometers of Ferdinand Berthoud, as part of on-going efforts to establish a more reliable means of ascertaining longitude.[10] The teams led by these three marine officers concentrated on measuring longitude and latitude and on more accurate soundings in harbors. The observations from the 1784-85 voyage of Chastenet de Puységur most closely match those found on the Saint Domingue plans of Phelipeau, though in several cases the longitude is found to differ by one full degree. Whether this was an error of transcription or Phelipeau was following some other unknown source remains to be determined.

Why the Maps of Saint Domingue

Considering Phelipeau’s maps of Saint Domingue in relation to Moreau de Saint Méry’s work explains several aspects of their production. The maps were likely designed to accompany both the publication of the Loix et constitutions and the next work on Saint Domingue by the same author, the Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie francaise de l’isle Saint-Domingue…par M.L.E. Moreau de Saint-Méry (Paris, 1797-98). Throughout the later work, Moreau de Saint-Méry refers either to specific maps or to the “Atlas,” which he explains in the Avertissement of the first volume: “The atlas I speak of many times in this work is however independent of it so that one might take one without the other; nonetheless it is easy to understand that a description acquires much more clarity with the plans and perspective views.”[11] References to the “atlas” within the Description point to plans included in the Recueil des vues. The Recueil, in its role accompanying the Loix et constitutions, was available to subscribers at a reduced price (title page: 48 livres en feuilles; 36 livres pour les souscripteurs). These subscribers are listed in four of the volumes of Loix et constitutions. Among them are three of the dedicatees of the four large Phelipeau maps of Saint Domingue: the comtes de Vaudreuil, Luzerne, and d’Agoult. And although the fourth dedicatee, the marquis de Castries, does not appear as an individual subscriber, as state minister of the Marine he may have been included in the large order from Louis XVI, who ordered 104 copies of the six-volume work.

Given these close connections, it is possible that Moreau de Saint-Méry financed the production, engraving, and printing of Phelipeau’s maps and views, which were sold separately or as part of the Recueil des vues. The engraving may have been executed in the workshop of Ponce or that of André Basset, at an address on the Rue St Jacques similar to Phelipeau’s. We suggest that Phelipeau was the compiler of the maps and plans based on the cartographic materials of local surveyors and engineers that Moreau de Saint Méry brought with him from Saint Domingue to Paris, and on the soundings and geodetic coordinates published from scientific marine voyages to the Antilles in the 1770 and 1780s.

[1] Extant copies of the map are few: Library of Congress, G4944.C3G46 1786 .P5, as linked, with decorative frame; William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Maps 8-I-1786 Ph, no decorative frame ; the Historic New Orleans Collection, Williams Research Center, Object File name: LP000321, colored but no frame; the Archives departmentales de la Gironde, 61/J 70/21/[1780], in a case, only the right half of the map, no frame.

[2] This same address appears on most of Phelipeau’s maps of Saint Domingue discussed below. On the privilège du roi see Mary Sponberg Pedley, “Privilege and Copyright,” The History of Cartography, Volume Four: Cartography in the European Enlightenment, ed. Matthew H. Edney and Mary Sponberg Pedley (Chicago, 2019), 1115-1119, esp. 1116 for France.

[3] Henri Berthaut, Les Ingénieurs-géographes militaires 1624-1831, Étude historique (Paris: Imprimerie de la service géographique, 1902).

[4] Jean-Louis Glénisson, “La cartographie de Saint-Domingue dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle (de 1763 à la Révolution),” thesis, École nationale des Chartes, 1986; “Topographical Surveying in the French West Indies,” in Edney and Pedley, eds., Cartography in the European Enlightenment, 437-9.

[5] The join of the papers printed from the two plates of the 1784 proof plate of Plan de la ville du Cap Français et ses environs may be seen running down the middle of the map; the join between the surrounding neat line and longitude frame is visible. See Ruderman copy.

[6] A proof copy of 1784 was offered for sale by Barry Ruderman. The copy at the University of Florida, Gainesville has no decorative frame and is in a boxed set with three other large plans, mentioned here: the Plan de la plaine du fond de l’Isle à Vache, the Plan du quartier de l’Artibonite, and Plan de la ville des Cayes.

[7] A digital image of the plans of Tiberon and St. Louis may be found in the Gallica copy of the Recueil des vues, 1791.

[8] Moreau de Saint Méry, Discours Préliminaire, Loix et constitutions des colonies françoises de l’Amérique sous le Vent, Paris, 1784, vol. 1, pp. xxiv-xxv.

[9] Glénisson, “La cartographie de Saint-Domingue.” Examples of their work may be found in the archives of the Service Hydrographique de la Marine, Bibliothèque nationale de France, and the collections of the Depot de la Guerre, Archives Nationales d’Outre Mer. See, for example, Plan de la plaine du Cul-de-Sac du Port-au-Prince, isle de Saint-Domingue levé / par Mr. de Hesse [ca.1780] ; Carte de la côte du Cap depuis le Carénage jusques et compris le port Français / Levée par le Sr. Rabié, …1746); and Carte de la plaine de Miragôane / Levée par nous, Off. d’Inf. Ingénieur Géographe des Camps et Armées du Roy, Sorrel, 1767.

[10] Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu, Voyage fait par ordre du roi en 1768 et 1769, à différentes parties du monde, pour éprouver en mer les horloges marines inventées par M. Ferdinand Berthoud….Paris, 1773; Jean Antoine Verdun, marquis de la Crenne, Voyage fait par ordre du Roi en 1771 et 1772, en diverses parties de l’Europe, de l’Afrique et de l’Amérique… Paris, 1778; Antoine Hyacinthe Anne Chastenet, comte de Puységur, Le pilote de l’isle de Saint-Domingue et des Débouquemens de cette isle … Paris, 1787. That Moreau de Saint Méry was familiar with their surveys is clear in the Description topographique: see, for example, vol. 1, 554, 705 (with coordinates of Fleurieu for Port au Paix).

[11] Moreau de Saint Méry, Avertissement, Description topographique,… de la partie francaise de l’isle Saint-Domingue (Paris, 1787), vol. 1, n.p.

Cite this post as: Mary Pedley, “René Phelipeau and the Plan de la Plaine du Cap François, 1786,” Colonial Networks (May 2025), https://www.colonialnetworks.org/?p=780