Sophia Kitlinksi (Yale University)

In the final years of King Henry Christophe’s reign over northern Haiti (r. 1811–20), a Black man arrived at Christophe’s royal court in the opulent palace of Sans-Souci. He sought artistic instruction under British painter Richard Evans at the recently established Academy of Painting and Drawing. To reach the Academy, the aspiring artist would have traversed a landscape still carrying the memory of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). He would, years later, render the ruins of plantations which lined the surrounding roads (Fig. 1).

The man’s artistic education was short-lived. Amid growing popular unrest, Christophe took his own life in his bedchamber at Sans-Souci in 1820. This cataclysmic event shuttered the Academy, and the curtains fell on Christophe’s kingdom. Yet the artist continued to reside in the region after Christophe’s downfall and produced new works of art. In 1827, two of the artist’s now-lost drawings were taken to England and made into lithographs by Scottish printmaker John Heaviside Clark. These lithographs appear in an 1830 memoir titled Notes on Haiti authored by Charles Mackenzie, who had served as Consul General of Haiti between 1825 and 1827. Mackenzie offers only a single acknowledgment of the today-unknown Black man’s contribution of the only two illustrations included in his ambitious six-hundred-fifty-page work: “The individual who made the sketches which are engraved in these volumes, is a native Haitian, who owed all his instruction to the institutions of the king.”[1]

Mackenzie frames Notes on Haiti as an objective report on Haiti’s social and political conditions, but his motives were overtly ideological. In the book’s preface, Mackenzie claims that his earlier reports had been used to describe Haitian society and its leadership favorably—prompting him to publish a scathing and often overtly racist rebuttal.[2] Mackenzie fills his text with gruesome accounts of the atrocities committed by Black leaders both during and after the Revolution while conspicuously omitting any mention of the violence of slavery. Mackenzie furnishes his visit to Christophe’s palace with particular prominence within the book, writing that the edifice was a “place in which, I believe, for a time, more unlimited despotism had been exercised than has ever prevailed in any country aspiring to Christianity and civilization.”[3] Within a narrative that relentlessly discredits the capacity of Black people for self-governance, it is striking that an artist who worked under Christophe created the book’s sole visual representations of the country.

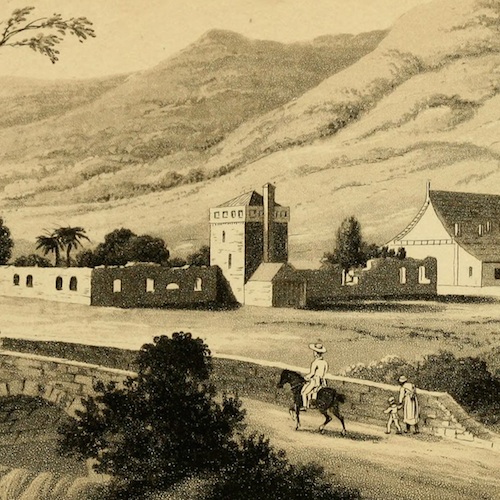

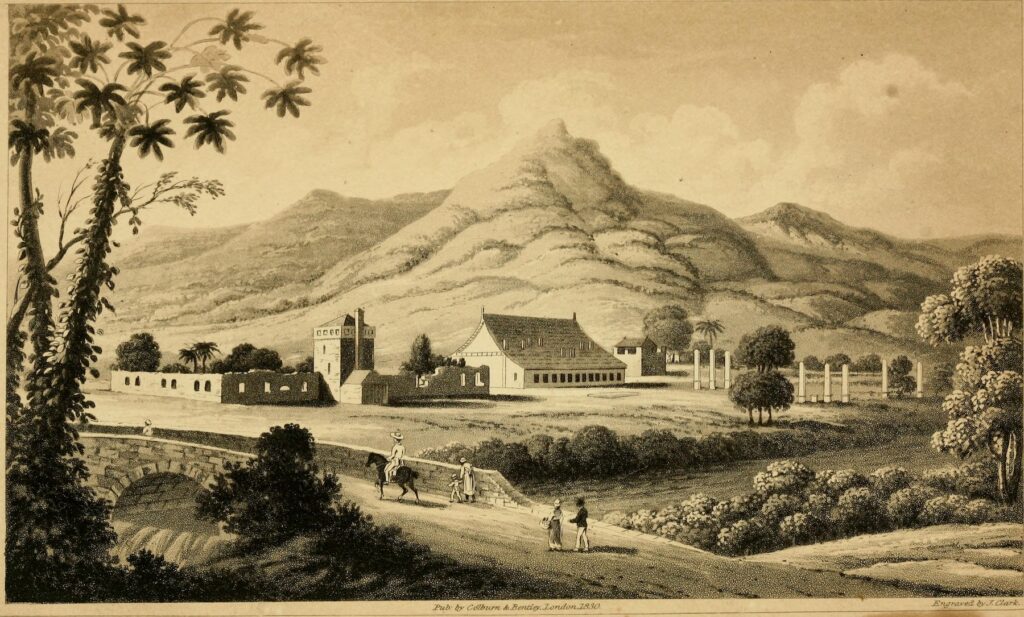

Mackenzie’s book includes two scenes: one depicting Sans-Souci and the other showing a road passing alongside the partial ruins of a former plantation (Fig. 1). As one of the most talked-about edifices in the world at the time of its construction, the image of Sans-Souci represented a predictable selection. However, the lithograph of the ruined sugar plantation adjacent to Sans-Souci initially appears incongruous. Mackenzie only makes a passing and imprecise reference to the plantation in his text: “We traveled over a tolerably good road, through the ruins of sugar plantations, of one of which the plate gives a very accurate representation.”[4] Even if Mackenzie requested an image of an abandoned sugar plantation, the decision to depict La Victoire likely belonged to the artist. What was his intention in drawing this scene?

The artist likely selected the site in reference to a key event in Christophe’s rise to power. In the final years of the Haitian Revolution, Christophe’s military rival Jean-Baptiste Sans-Souci—an ethnically Kongo rebel leader—rose to prominence between 1802 and 1803. Sans-Souci amassed a wide, primarily African-born following and thus challenged the emerging post-revolutionary political hierarchy led by Christophe, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Alexandre Pétion. Although Sans-Souci had pledged his allegiance to Dessalines, Christophe lured Sans-Souci to his camp on the Grand Pré plantation and murdered him—an act which consolidated Christophe’s power.[5] The title of the work, “La Victoire, formerly Grand Pré,” explicitly articulated that the plantation’s current name had changed from that which we can distinguish on René Phelipeau’s map. The renaming of an abandoned plantation may appear illogical, but the choice of a name that can be translated as “The Victory” for the precise location where Henry Christophe defeated Sans-Souci was almost certainly calculated. While the moment of Christophe’s triumph is not visually represented in the lithograph, the site evidently served as a monument to his victory. When paired with the drawing of the palace of Sans-Souci, the scene forms a diptych demonstrating Christophe’s authority, even years after his death.

The renaming of the abandoned plantation is just one example of the ways in which Haitians remapped the plantation terrain after the end of the Revolution, exerting their control over the landscape and eliminating signs of French colonial rule. This transformation commenced with the nation’s name: Saint-Domingue would be re-baptized Ayiti, the island’s Indigenous Arawak name, meaning “land of mountains.” Christophe also baptized the wealthy port city near his palace (formerly called Cap-Français) Cap-Henry in his honor. Yet the Haitian artist not only invoked the changing of a social order away from white supremacy in the lithograph’s title—he also showed it in the scene itself.

The lithograph of the artist’s drawing presents a striking departure from the plantation’s appearance under slavery. The image shows a babbling brook with an arched stone bridge, a woman patiently accompanying a child along a road, and the poetic backdrop of hills. Likely drawing on Evans’ artistic instruction, the artist uses the familiar visual tropes of the English countryside to portray a bucolic Haitian landscape. The Black figures walking by the plantation on the road are occupied with conversation, the restraint of a rambunctious child, and travel on horseback: not a single figure pauses to gaze at the ruined plantation buildings to their right, their bare terrain devoid of the quotidian labor of the plantation. The figures’ apparently uninhibited mobility represents an act of freedom incompatible with Haiti’s slaveholding past. In the hands of the Haitian artist, the plantation transforms from a relic of slavery to a backdrop to Black freedom.

Cite this post as: Sophia Kitlinski, “Drawing the Legacy of Henry Christophe,” Colonial Networks (June 2025), www.colonialnetworks.org/?p=835.

[1] Charles Mackenzie, Notes on Haiti: Made during a Residence in That Republic, vol. 1 (London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1830), 158. Mackenzie consistently uses the term “native” to refer to anyone born in Haiti, with the implicit understanding that a “native Haitian” would be Black; he refers to exceptions as “native whites.”

[2] Ibid., vii.

[3] Ibid., 170.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Michel-Rolph Trouillot contends that Christophe’s palace was named after Jean-Baptiste Sans-Souci. Trouillot links Christophe’s selection of the location and name of his abode to a practice in the West African kingdom of Dahomey, located in what is today Benin. There, military leaders founded their palaces in locations where important enemies had been defeated and killed and then baptized the edifice with their names, part of a “transformative ritual to absorb [their] old enemy.” See Trouillot, Silencing the Past, 2nd ed. (Beacon Press, 2015), 211.